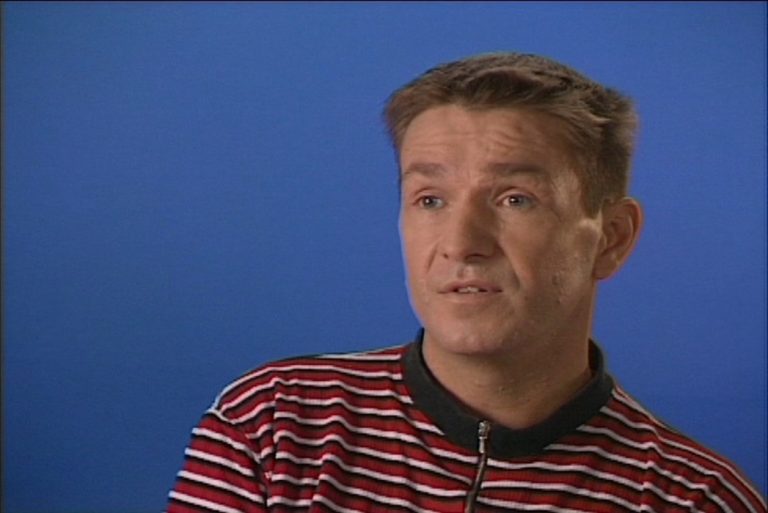

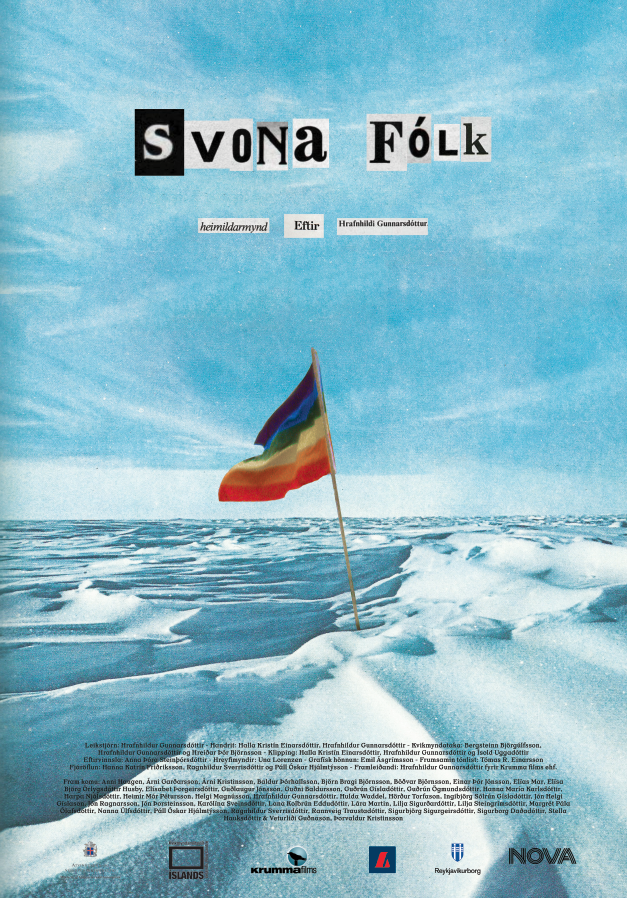

Svona fólk – Plágan or People Like That – The Plague, documentary about the HIV epidemic in Iceland will be shown at cinema Bíó Paradis this Sunday, as a part of Reykjavík Pride 2019. Donni Gíslason is one of the people who tells his story in the film. Donni tested HIV-positive in 1985, when he was 25 years old, and ten years later his immune system had collapsed, he was losing his eyesight and the doctors told him he had, at most, three months to live. Then a miracle happened.

New HIV drugs arrived and after a bit of a struggle Donni was put on a medication cocktail that saved his life. His vision is still impaired but the HIV virus is no longer detectable in his blood. How does it feel to be given a new lease on life after a death sentence?

When Donni tested positive for HIV back in 1985 there was a lot of prejudice and fear for AIDS in society and he says some people treated him like he was radioactive.

“It was a a huge stigma,” he says. “There was a lot of fear and uncertainity regarding AIDS in that time, as it was a new disease and nobody really knew for sure how it got transmitted and how it would evolve.

I am lucky enough to have a very supportive and understanding family and they all supported me as best they could. The information people got about the disease and the risk of getting it was very misleading at that time, people thought they had to take all kinds of precautions to be able to avoid getting infected from someone who had tested positive for HIV. It was a bit mental.”

“Other gays treated me like I was radioactive and didn’t want to go anywhere near me.”

Donni says that when people talk about these times now it is sometimes forgotten that other gays also regarded HIV as a stigma and much fear governed the gay community.

“Other gays treated me like I was radioactive and didn’t want to go anywhere near me. Some would even take the stand of warning others about who might possibly be infected of the PLAGUE as some liked to call it, be it true or just plain gossip. That was a shock for many of us and it hurt deeply and it shattered to a degree our small gay community at some point,” he says. “But my real friends stuck by me and I did not lose any of them, I’m grateful for that.”

Never believed he was dying

Getting diagnosed with the HIV virus was in that time a death sentence, there was no cure and even the doctors did not know much about the disease. Donni says that inspite of that he never really believed that he was going to die.

“Somehow I managed to cling to hope through this all,” he says. “I did not have any symptoms for years, even though the virus vas detected in my blood, but I never felt that I was ill. It was not until almost ten years after the diagnose that I started to lose my health.”

One of the consequences of the disease was that ten years after the diagnose Donni started to lose his eyesight as a result of his immune system collapsing.

“In 1995, eight months before the first HIV drugs were made available, I went in to the stage of full blown AIDS,” he explains. “When they became available in Iceland my doctor did not want me to have them as I was too far gone with the disease. It was thanks to another doctor, Anna Þórisdóttir who had specialised in the disease, that I was allowed to try the new drugs even though I was considered an incurable case.”

At that stage Donni and his family were prepared for him passing away in a few weeks, but he says it never felt real to him that he was dying.

“The immune system had totally collapsed, I was down to 55 kilos, the family had been summoned to a meeting with the doctors to hear the death sentence, but as weirdly as it sounds I never really believed it deep down.

“It was a fantastic feeling. But it also felt unreal and for a while I went into a crisis not knowing what I was supposed to do with this new life.”

I paid lip service to the doctors and sociologists who were telling me this, but I never felt that I was really dying. I had gone for all kinds of holistic medicines, drank a lot of herbal concoctions and tried everything I possibly could think of to counteract the disease. I had all the medical attention and stuff in my home for the last six months of this period and when my family went to the hospital to discuss my death I stayed at home and painted the kitchen walls.

I just found the thought of dying absurd, even though I had already said goodbye to a lot of my friends who had died from the disease. Looking back it feels as I was in somekind of bubble where the reality of it did not reach me.”

A new lease on life

Donni says that he has always been a fighter and he just was not ready to lose the fight with death. Even his deterioating eyesight did not put him off the fighting track.

“When my immune system had collapsed completely, I was told I had two T-cells in my body at the time instead of the 6-800 T-cells you have when you are fully healthy well, but I told the doctor that I visualized these two T-cells working out at the Gym and they would conquere in the end. The most serious effect of this collapse of the immune system was that a virus which is called CMV, which a lot of people have in their bodies but is not doing you any harm if you are healthy, started attacking my eyesight which was a known side effect of AIDS. The doctors tried to put me on medication for that, I had to get liquid drug in my veins for four hours every day to try to keep my eyesight. The thing is, and it was probably an oversight by the doctors not to realise it at the time, that when I started to get the drug cocktail for the AIDS they kept giving me this drug for my eyes, which I was told years later was a mistake and that part of the reason I am visually impaired was caused by the counteraction of these different drugs. I don’t blame anyone for this, it was all such a new territory for the doctors that they could not have known.”

The recovery was quick, a year after the treatment with the new drugs started Donni was fit enough to start travelling and start life a new. How was the feeling to be able to do all the things he had stopped being able to do and no longer have death hanging over his head?

“It was a fantastic feeling,” Donni says. “But it also felt unreal and for a while I went into a crisis not knowing what I was supposed to do with this new life. I also experienced survivor guilt; why was I given a new lease on life when so many of my friends had died? It is a known syndrome with survivors, both from diseases and wars, and it was a very profound experience to go through. It was not until I went for a visit to my friends in the States for two months that I could get rid of the guilt. I met a lot of people who had been diagnosed, went to meetings at AIDS organisations and got a better feeling for how it had effected people. It was really liberating to see the whole picture of how the disease had evolved, not just the Icelandic side of it.”

Dedicated single

Donnis eyesight continued getting worse even though he got better from the disease and ten years later he was declared legally blind, which is defined as sight below 10%. He says that of course did limit his choices of education and jobs, but that he has never let that handicap stop him.

“I studied to become a counselor for blind people and that is my job today,” he explains. “I am a recovering alcholic and have been for twenty years now, and the support and self work I have gone through to get sober has helped me enourmously, both while I was sick and when I started getting better. So I have experienced it myself how important it is to have good counselors when you are battling some kind of difficulty.”

Donni is one of the people interviewed in Hrafnhildur Gunnarsdóttir´s documentary series Svona fólk or People Like That, a part of the project titled Svona fólk – Plágan will be shown at cinema Bíó Paradis this Pride and even though he is very open about his experience of the disease and recovery he admits that one question the film maker asked him on camera made him somehow uncomfortable.

“She asked me if it had affected my love live to have been an AIDS patient and must admit it caught me little off guard, how does one answer that?” he says. “After she left I started wondering if it had made me more of a loner, but I’m not sure. I have thought about it, of course, but I have always been a loner in that sense even though I’m very social, and I don’t think that has gotten worse by the disease. I find it harder to connect to people as I get older, I’m a homebody and very happy in my own company. I never understood this pressure from society that everyone should be in a relationship. I don’t think that suits everyone. The longest relationship I have been in was when I was HIV positive and it lasted for ten years, so I don’t think the diagnose made me afraid of love. I have a very good life today, I like my work, have a wonderful family and friends and I don´t really feel any need for a close relationship. That has nothing to do with being an AIDS survivor, it’s just who I am.”