A PhD student in History working on a research paper on the AIDS epidemic in Iceland has made interesting findings. GayIceland speaks to Hafdís Erla Hafsteinsdóttir about her research and discoveries.

The AIDS epidemic began more than 40 years ago and still continues to be something many of us can learn from today. HIV/AIDS remains a significant global health issue, underscoring the importance of continuous research, education and awareness efforts.

The epidemic has taught us about the vital role of early detection and treatment, the need for comprehensive and inclusive public health strategies, and the power of stigma in hindering these efforts. Furthermore, it has shown the critical importance of global cooperation in combating health crises. As such, while we have come a long way since the onset of the AIDS epidemic, there is still much to learn and apply from our ongoing battle against this disease.

There are few, if any places on Earth that don’t have some kind of connection to this global health issue, including Iceland. The first case of HIV in Iceland was reported around 40 years ago and although the population of Iceland is small, the impact of the epidemic was still evident.

Often when we tell and hear stories about HIV/AIDS, we tend to focus on larger, Anglo-Saxon countries like the USA, the UK and Australia; but the reaches of HIV/AIDS don’t really know the bounds of national borders. In Iceland, there are many worthwhile experiences, stories and lessons from the epidemic that can inform us and teach us and one particular resident is looking into exactly this. Hafdís Erla Hafsteinsdóttir (she/her) was born and raised in Iceland’s capital city of Reykjavík. She is a historian by trade with a special focus on 20th Century history, specifically gender history and the history of sexualities.

Hafdís has been working on a research paper looking at the AIDS epidemic in Iceland and GayIceland was lucky enough to sit down with this busy PHD candidate to find out more.

GayIceland: What is your research paper specifically about?

Hafdís: “The short answer is that it’s about the AIDS epidemic in Iceland. The slightly longer answer is that the research paper is looking at how the discourse on AIDS in Iceland was created and maintained.

To give some examples; throughout the AIDS epidemic, many words were used in Iceland to describe it like; kynvillingaplága (sodomy plague), eyðni (destruction) and alnæmi (omni-sensitivity), each of those words encompasses a different reality.

Kynvillingaplága is an attempt to create a group of outsider deviants. Eyðni is a panic word, designed to create and maintain fear; while the term alnæmi seeks to establish a more neutral meaning by using terms generally considered neutral or even positive such as ‘sensitivity’ to name the disease.

Discourse on AIDS had a huge influence on the reactions of the public towards the disease. Those who saw AIDS primarily as a “sodomy plague” threatening to destroy the world advocated for harsh measures such as a homosexual registry, isolation and the imprisonment of “irresponsible” people. Those who saw AIDS as a viral disease rather than a moral contamination were more likely to advocate for preventive measures such as sex-education, condom usage to mitigate the spread of the virus.”

GayIceland: Why did you feel you needed to do this research?

Hafdís: “I’ve been doing various research and projects in the field of what we can call “queer history” for the past seven years. Very early on it became clear to me that much research was needed on the AIDS epidemic in Iceland because little or no historical research had been done on it, especially its early years.

I was aware beforehand of the hostility from the media towards AIDS and those infected, but I was taken back by the blatant continuous misinformation and homophobia and how certain media outlets unashamedly continued to create fear and hatred and even took pride in doing so.

On a more personal note, when I took my first steps in the queer community in the 00s, I noticed how little space was given to the AIDS pandemic. When it came to celebrations of legal milestones such as ein hjúskaparlög (marriage equality) in 2010 which often required reflection upon history, it sometimes felt as if the AIDS epidemic had hardly happened; it was reflected upon through personal tragedies rather than something that effected the community as a whole, which is a bit of a sad detour from progress.”

GayIceland: Is there anything in your research that has surprised you?

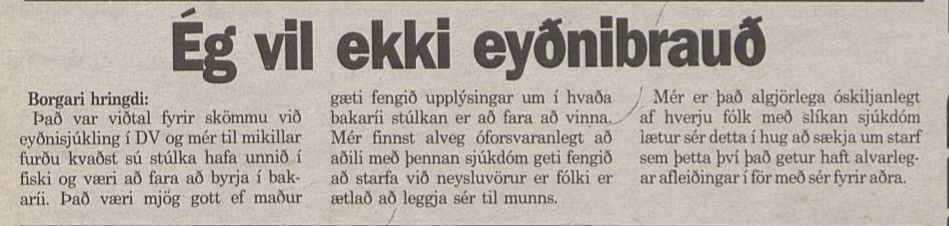

Hafdís: “I was aware beforehand of the hostility from the media towards AIDS and those infected, but I was taken back by the blatant continuous misinformation and homophobia and how certain media outlets unashamedly continued to create fear and hatred and even took pride in doing so (Yes, DV* I am referring to you!).”

*For readers based outside of Iceland, DV is an Icelandic news publication; during the AIDS epidemic it was the most read and trusted news source in the country with a 64% readership.

Public anxieties regarding Aids took on many forms. Not surprisingly for Iceland, many people were concerned about the safety of the public pools. This particular reader however was furious over the fact that a HIV positive person was employed in a bakery and called for the removal of all HIV positive people from the food industry. Such outcries were common in the media even though means of infection were well known.

Hafdís: “In the face of such an abundance of hate, the silence of the silent majority becomes very loud. But on a more positive note, the research also gives me an opportunity to explore how AIDS forced individuals and institutions to confront their own homophobia and slowly begin to change their attitudes, policies and opinions.”

GayIceland: How was the AIDS epidemic different in Iceland to larger countries like the USA or the UK?

Hafdís: “Part of the grand narrative of the AIDS epidemic in the US and UK is that it led to increased hostility between the state and LGBT+ organisations. The mentality of the Thatcher/Regan era created a polarisation. It was a bit different in this part of the world; in Iceland and the Nordics in general, the opposite development occurred. The AIDS epidemic brought the state and LGBT+ organisations closer together, established a channel of communication which started to yield important legal reforms in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This is a good (and important) reminder that when we look back at the past of this epidemic, there tends to be a dominance of the English-speaking, Anglo-Saxon queer experience of it; but there were many different experiences happening all over the world.”

Before AIDS, Iceland hadn’t really taken any steps towards the legal and social status of homosexual people.

GayIceland: Are there any interesting things you discovered in your research?

Hafdís: “Yes! I have found that there was a direct connection between the AIDS epidemic and citizenship. The epidemic revealed the marginalisation of gays and lesbians. (Unfortunately, at the time, trans people and bisexuals were still on the fringes of the community, so their experiences didn’t receive the same attention. Trans people were invisible and bisexual males were commonly seen as closeted gays and a potential for cross contamination between homosexuals and heterosexuals.) Basically, people within the queer community were well-aware of AIDS but the government hadn’t really engaged with them before. To put it simply, the government wanted to control the epidemic and in order to “control the gays,” they first needed to admit that gay people existed and that they were citizens of Iceland who deserved the same protections from an epidemic as everyone else. At the time, Iceland differed greatly from the other Nordic countries who, in very simple terms, were a little bit further ahead in their ways of thinking. Before AIDS, Iceland hadn’t really taken any steps towards the legal and social status of homosexual people.”

“The news paper DV and the journalist Eiríkur Jónsson played a crucial role in escalating the Aids panic in Iceland. The yellow press fed off posting sensational headlines calling for increased surveillance, isolation and even imprisonment of what they deemed as “irresponsible” aids patients,” says Hafdís Erla.

GayIceland: What impact has this period of time in Icelandic history had on the lives of LGBTQIA+ people in Iceland today?

Hafdís: “Words cannot begin to describe the impact on those who lost their loved ones, family members and friends. The way I see it, it is a generational trauma but also an enormous (albeit overlooked) catalyst of change. We also must not forget that AIDS is not over, or done.”

GayIceland: There was recently a memorial where the prime Minister apologised for the treatment of AIDS victims and their families back in the day; but was that enough? There has been an ongoing discussion for some time that the government should publicly apologise. What are your thoughts on that?

I believe that any dialogue about AIDS should be led by those who survived the epidemic and in the memory of those who didn’t.

Hafdís: “Public apologies can be a double edged sword. They can easily turn into hollow words used to keep sweeping an uncomfortable past under the rug. But they can also be meaningful. I believe that any dialogue about AIDS should be led by those who survived the epidemic and in the memory of those who didn’t.”

GayIceland: When do you expect to finish your research paper and publish all the findings?

Hafdís: Laughs. “Do not ask a striving PhD student that question!!!”