Oktavía Hrund Jónsdóttir is back in Iceland. Permanently. That is one of the reasons she has agreed to talk about her work as a queer activist to a web magazine, with her picture next to her name. Because her work has taken her to places where being queer is not only dangerous to your status and possibilities in society but simply life threatening.

Oktavía defines herself as queer in the sense that she will not be labelled. She grew up in Iceland and Denmark and has lived in the USA and Germany as well. And she has been an activist for quite a while.“I have always had a very strong sense of right or wrong and freedom of expression and the question of privacy has always been important to me. In school I was always with the weird kids, hanging around in the basement and smoking, fighting bullying and creating safe spaces, both inside and out. That’s where my activism kind of started and it has taken me to many weird and wonderful places.”

Oktavía studied communication and international development in Denmark where an opportunity for professional activism presented itself. “In 2006 I started working for a media development organisation that was fostering and strengthening independent media all over the world. I was working in security and quickly realised that security is a lot of things. It is not just about being safe from physical harm; there are a lot of psychological things involved in activism and in that sense the internet for instance, with all its good qualities, is a very open and unsafe venue.

“In some parts of the world, what apps you use … is quite dangerous and if you use the Internet a lot, whether it is to do your activism, or to hook up, you are directly targeted.”

And I started to become more interested in identifying people who needed more help. For example when you are queer a lot of the time society is against you. Sometimes there are even laws against you. The usual things that people do to keep safe don’t work for queer people. Normally your security comes from your network, your parents and the activities that you do, but those are the areas where queer people become isolated, they can’t tell their parents that they’re out, can’t talk to their friends about who they are.“

Being queer in the Middle East can be easier

About four years ago Oktavía started The Safe Initiative where she works with physical, digital and psycho-social security. “That led me into communications with queer communities throughout the world. In some parts of the world, what apps you use, how you communicate and what you communicate, in fact just being yourself is quite dangerous and if you use the Internet a lot, whether it is to do your activism, or to hook up, you are directly targeted.”

Oktavia has worked in Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia and the Middle East. “For me getting the message through has always been the most important part so when I travel I adapt as much as I can. I’m often a lot taller, a lot whiter and have a lot more freckles than most people in these places, I can’t run away from that, but I try not to draw any attention to myself, my hair, clothing etc, try to blend in. I need to be able to spend time with people to get the message across, and getting to a place where the way I look isn’t the main focus, so I sometimes wear a hijab or niquab to take the focus of my whiteness.”

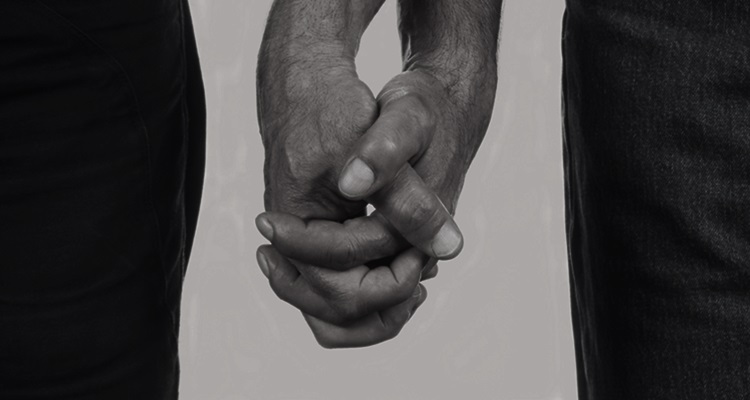

Being queer in the Middle East can be easier in some ways, she says. “There is a culture of touching, so two men can walk down the street and hold hands or grab each others buttocks and that is not looked upon as being weird but obviously being a gay man or whatever you identify as, is super tricky. It is not a long process from someone being outed, to death. And the family shuns you and forces you into rehabilitation programmes. And a lot of kids don’t make it through that. But that happens in the US too.”

Oktavía’s main focus has been on doing courses for groups of activists, who are queer or trans but can’t be themselves when they are at home. That work is dangerous for many reasons. “Together we have to find a safe place and create a safe space and it takes time for people to trust and find safety in order to be themselves. So you can’t run a super tight workshop. You always need at least a couple of days to bring people out of the reality of constantly looking over their shoulders.

“It is not a long process from someone being outed, to death. And the family shuns you and forces you into rehabilitation programmes. And a lot of kids don’t make it through that. But that happens in the US too.”

In the workshop we spend a lot of time creating a space where people can be themselves and share experiences, where we all agree on conduct, what we allow, what we don’t allow and then we have to make space for those emotions that have been suppressed for so long to come out, to exist and to close again. Because people do have to go home again and that can be hard. We talk about safety and what works in what contexts both with physical safety and internet security.”

Interrogated on the Syrian border

One of the things that Oktavía does is reminding people why they do what they do, rediscovering the passion that started their activism to begin with. “Being an activist is really not an easy job and you need to remind yourself why you aren’t an accountant, why you didn’t just get a husband and kids, hide who you are and make everyone happy. We make choices and the choices we make define us. So a lot of the psychological work is based on helping people rediscover that passion and reminding people that are they’re not in prison, they’re not dead, so clearly they’re doing something right. And then there is of course physical security, what to do with stalkers, or when the police starts to harass you or rape you, what do you do when threatened with violence. The queer groups also have to know how to deal with the people who are closest to them because the biggest threat can come from family or old partners.”

Oktavía admitts that she has sometimes gotten into trouble. “I haven’t always told my mom what I was doing. I know that I’m being tracked by authorities in some countries and I very often get extra attention on borders, not only in the Middle East, the US is pretty difficult too. I have smuggled information across borders, I’ve slept in bathtubs because of attacks outside. I have been interrogated. I once spent four hours on the Syrian border just saying my name and profession over and over again. I’ve been really sick, and sometimes when you have one shot at helping people in a remote area where people are taking huge risks to meet you, being sick isn’t an option. So you are passing out on the bathroom floor trying to make it go away. And then you start negotiating with yourself: “Do I really need to go to hospital? ” And so on. I’m also always concerned that it’s not only about my safety. That I’m putting the people that I’m in contact with in terrible danger by meeting them.”

And she has also had enough. “I was in the mountains of a certain country. I had been travelling a lot, and working a lot and heard a lot of difficult and heartbreaking stories. You also sometimes lose the people that you have been trying to assist, people who have become close to you and it adds up. I was there working with a trans activist and a women’s right activist and there was someone in my hotel room every day, going through my stuff. You learn very quickly to detect when someone has been in your room. And that night I went through my usual panic, did I ensure all safety, both for myself and the people I was working with? And then I sat down on my bed and thought: “I can’t do this anymore.” I just wanted to go home. But then I got over it.”

The interview is coming to an end and I ask Oktavía where I can find more about her work on the internet. She shakes her head. “There is nothing about me online. I ran for parliament for the Pirate party for this election and that was the first time a picture of me next to my name went on the Internet. And I was very reluctant to make it so. There is no and will be no relevant information on me and my work on the Internet because the stakes are so high. There are people’s lives on the line.”

“I have smuggled information across borders, I’ve slept in bathtubs because of attacks outside. I have been interrogated. I once spent four hours on the Syrian border just saying my name and profession over and over again.”

So how do people get in touch with her? “You set up a code and pretty soon you have a safe line to someone. Word by mouth, queer communities work a lot like that, especially where they are not allowed to express themselves openly, and the need is so great that there is constant demand. People who travel meet with these groups and then contact me with methods of communication. I’ve been doing this for ten years and have discovered that the world can be a very small place.”

*Oktavía has retired from giving courses for the time being and was therefore willing to give this interview. She still continues to advise official organisations throughout the world and is on several boards and consulting committees regarding safety and the right to privacy.

Main photo: Maintaining a sense of humor and not taking everything too seriously all the time is essential in the kind of work Oktavia does.