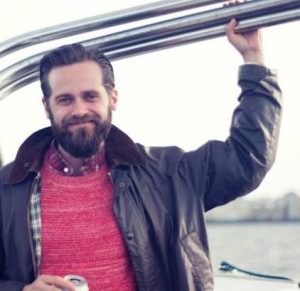

A princess who’s brave and resourceful instead of being a passive, pursued object. And a prince who has zero interest in girls. Tonight the Student Theater will stage a brand-new version of Cinderella or rather a consciously anti-Cinderella: Ashfall (i. Öskufall) which addresses queer issues and equal rights. We met with author/director Tryggvi Gunnarson and started by asking why this long-loved fairy tale was in dire need of a drastic make over.

“Well, not many people know this but the original Cinderella story is a completely different from the version most of us know and versions of the original can be found in various cultures. That story was told by women, to other women, teaching the importance of not betraying women – their fellow sisters – and especially not betraying the family,” Tryggvi explains.

“In those versions Cinderella is often way tougher, sometimes almost cruel and even the one who kills her mother, with the help of the stepmother. But repents when she realizes how much trouble she’s in and through that repent she gets assistance from her mother’s ghost. Often limited help, so she has to be really smart and find out the solution herself.

However through Charles Perrault’s version (1697) and later the Brothers Grimm version (1812), Cinderella’s character is transformed into that silly little thing, pretty and sweet, who gets saved by the prince, because she’s a good girl and does what she’s told. That resulted in the Disney version (1950) which crystallizes that stereotypical gender role which is so damaging to everybody. Unfortunately that’s the version that we let our kids watch every day.

We at The Student Theater (i. Stúdentaleikhúsið) wanted to try to see what happens if we defy this old version of gender roles. What happens if we refuse to accept these rules of beauty and the fact that Cinderella is supposed to be a good and obedient girl. What happens, if instead of a king and queen, there’s a king and king.”

Wait – a queer prince?

“Yes! (Laughs) That is sort of the heart of it all. The play is about being queer. Thankfully in reality the younger generations are always more and more accepting to the fact that being queer shouldn’t be an issue at all. But what happens if you put that non-issue into this stereotypical Disney-fairy-tale world that it doesn’t fit into? In the play we’re dealing with the conflicts that could arise from that and how dangerous stereotypical roles are to us.”

“The biggest problem with popular culture especially Icelandic theater – which seems to be decades behind what is actually happening in Icelandic society – is the queer image.”

Talking about queer issues, do you think that they are addressed adequately in Icelandic theater?

“I’m reluctant to say it, but no. The biggest problem with popular culture especially Icelandic theater – which seems to be decades behind what is actually happening in Icelandic society – is the queer image. In Icelandic theater queer characters are all too often comic figures: “Oh my, they think I’m queer, that’s so funny! Haha!” The audience is supposed to find that so funny, because what is more embarrassing than someone thinking you’re queer?!

Icelandic theater needs more strong female characters and strong queer characters. Plays shouldn’t only portray queer people more often – it’s always a good thing if they do – but the way that they’re portrayed also matters. Simply as that, queer. Not as any sort of issue, just a simple fact, because that’s what it is. Far too often queers are in a play because of some arbitrary factor, not just as characters, as a part of society. That is not done enough. If ever.”

Going back to your own play, Ashfall, would you say it is closer to a drama or a comedy?

“It’s no farce, but there are dramatic scenes along with scenes we hope people will find extremely funny. As with all good stories, it’s a mixture of both.”

A satire maybe?

“Completely! But we don’t want to preach anything. We’re not telling the Icelandic nation how to think or behave. We can’t because we’re not perfect either. We’re not free from these gender roles or images. They’re something that we learned from our parents who also learned them. But, by putting this play on stage, we want to face ourselves, our own childhood, and our society, and make us admit that there is so much wrong going on.

For example, some of us went to the protest in front of the police station last Monday (held because two men charged with rape were not held in custody) and afterwards went to rehearse a scene, written long ago but eerily similar to some of the things going on right now. Like phrases one of the guys has been writing to young girls online. That was tough.

In short, our society has this malady that we want to fight. But at the same time we’re afraid what that could mean. If you cut the wen, what will seep out of it? We at The Student Theater are not trying to pretend to be any better than anybody else. But there is something wrong with our society, and we’re a part of it and we all must try to fix it.”

Tryggvi says that he is however filled with optimism after working with the young people at The Student Theater (i. Stúdentaleikhúsið) and how open they are about equal rights and about queer issues. “This is way more natural to them then when I was their age. Just an example, when I was in high school, I asked for a video camera because I wanted to make a short film but was laughed at and told to play football with the other kids and stop being so foolish. My girlfriend teaches in high school and her students are now making feminist-rap! So we don’t have to worry. The times have changed, for the better I think. This is all changing for the better.”

Talking about younger generations, can children come and see the play?

“No – it’s not suited for children under the age of 12, mostly because of the language and talk about sex, even violent sex. But I truly believe that teenagers would benefit from seeing it. Everybody could benefit from seeing this actually. But to be clear, this is not a children’s play.”

Do you think a children’s version could be made?

“Yes, absolutely. This is an exciting mine-field to step onto! So many of us love these old fairy tales and have no idea about the hidden meaning or agenda they have. Some say that we learn our social values in different stages. First by the “yes and no” from our parents, then from stories and fairy tales, later from horror movies and finally, when we are grown ups from TV-sitcoms. So, to take a popular fairy tale and tell people: “Hey, remember that beloved fairy tale your parents used to tell you? It’s complete bullshit, sorry!” But I don’t think I’m the best candidate to make the children’s version, I’m probably a bit too brutal for that project.”

Are there any other fairy tales that could do with such a make over?

“All of them! All these stories and fairy tales are simply bizarre! The female characters are almost always victims. A beautiful Gilzenegger princess almost in formaldehyde, put in jar upon a mantle, where we can admire her but not touch, because she could break. The price is almost always some sort of man. And the story-line is basically always the same.

And many artists have already tried their hand at turning these stories upside down, I’m not inventing the wheel here.”

Now the play is in Icelandic, but you seem to think that the meaning transcends language?

“There is a lot of text, but I’m sure that people who don’t understand the language will have a lot of fun. If not just for the sheer experience of seeing a play performed in an old, former storage for bombs (now referred to as “gömlu kartöflugeymslurnar”) at Rafstöðvarvegur 1A built by the American army in the forties.”