Icelandic photography school student uses a queer man’s blood to raise awareness surrounding the blood donation bias.

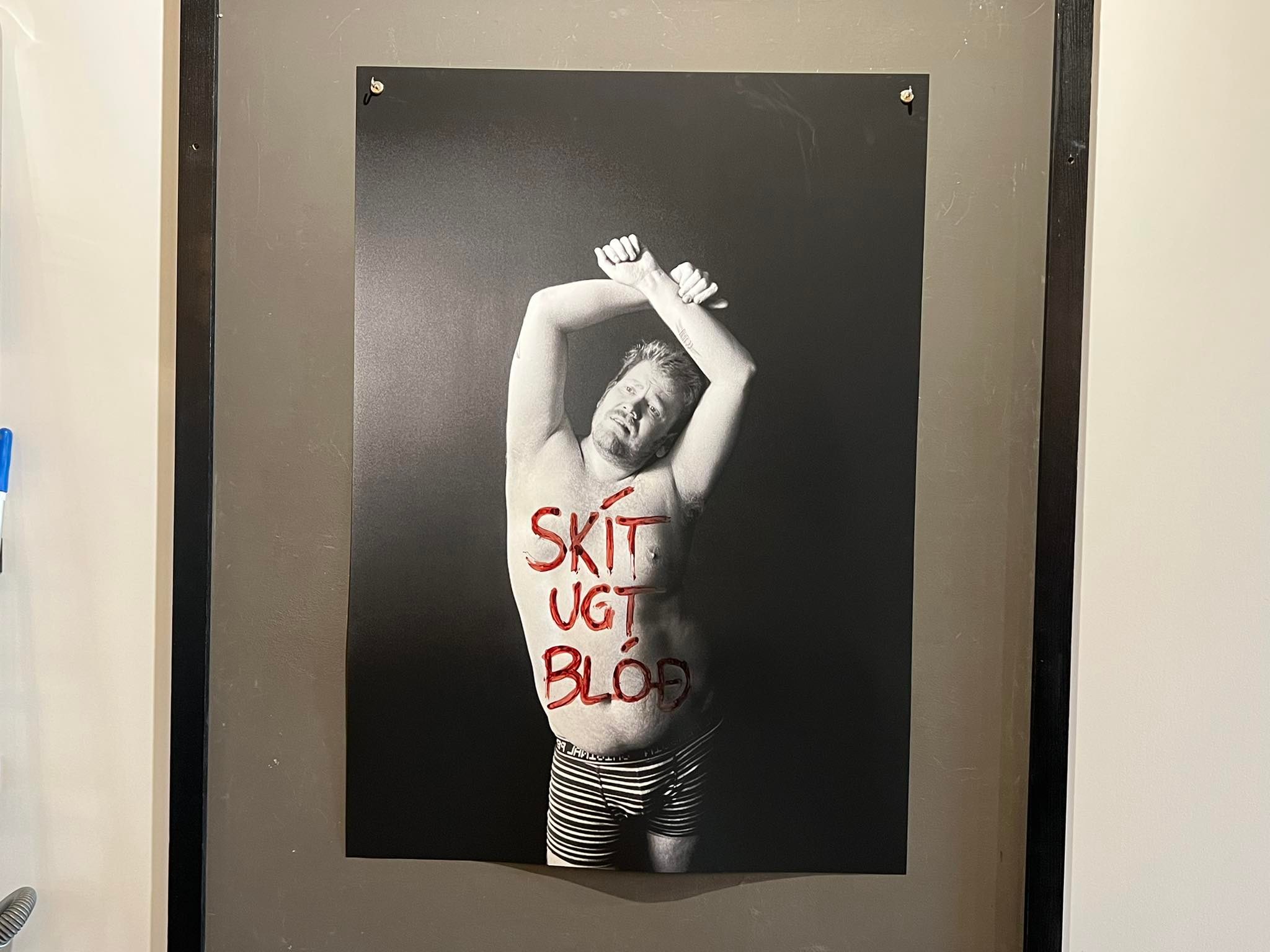

In a provocative final assignment for her first year in The School of photography (Ljósmyndaskólinn) student Heiðrún Fivelstad has chosen to shine a light on blood donation laws in Iceland. The artwork, entitled “Skítugt Blóð” or “Dirty Blood,” is a photo of a queer Icelandic man with the words “Skítugt Blóð” painted over it in real blood.

The blood was donated by another queer man to drive the artist’s message home. The prompt for the project was to take something she’d already been working on and push it one step further. Heiðrún’s original piece was just the photo of her subject on its own; the blood was added to enhance the message she wanted to convey.

Pose, pose, pose

“We were learning about art history and there’s a saint that came up, his name is Saint Sebastian,” she says. ”He was portrayed very homoerotically, very gay, and that intrigued me. He was a Christian during the Roman era and was sentenced to death because of it. He was stricken with plague-infected arrows, but survived the execution and was nursed back to health. The paintings show him as a young, attractive male stricken with the arrows, but he always seems unfazed by them.” She notes, clarifying “he’s shown like a twink,” she laughs.

“The search results come up with headlines that read “gay men are finally able to give blood,” but it’s all about the proposals. It’s all of these huge positive titles like “Proposals for a bill for a one year period blah blah blah” and it hasn’t gone through. And it’s been years which is annoying!”

The story of Saint Sebastian was the original inspiration for the piece before it was pushed the extra mile. Svenni (Sveinn Snær Kristjánsson), the subject of her photo, is holding a similar pose but was chosen as an updated interpretation of Saint Sebastian. “[The Saint] is always shown as this buff or twinky guy but with my work, I wanted to do a modern version of that, a modern version of what a queer man looks like today,” says Heiðrún. Body positivity and weight stigma in the queer community are also themes in the piece. “So he’s queer and he’s plus size and he’s a beautiful model to photograph. It’s a modernized version of what we consider to be a queer man. I wanted to take it all the way.”

Heiðrún’s work also coincides with the ending of one plague and speaks to another plague the queer community has faced. “Saint Sebastian was popular in the middle ages because he survived the plague of the time that he was infected with by these arrows. During the AIDS pandemic, he became a super popular inspiration for queer artists as well. They used Saint Sebastian as an inspiration of being infected with the plague and overcoming it,” she says.

Queer men still banned completely

For Heiðrún the covid pandemic provided another lens through which to interpret the AIDS crisis and the stigma surrounding infection, just as the plague that Saint Sebastian was infected with. It put into sharp focus the discrimination queer men (and those that have sex with them) face when it comes to donating their blood. “I was looking at archival news coverage and found an article by Bjarni Snæbjörnsson that he wrote 20 years ago and still applies today. Every word still applies. They were calling for more blood and he was saying that he can’t go and give blood because he’s gay,” she says.

To her surprise, nothing about the rules on blood donation has changed in those 20 years. She explains “I thought that there was this proposition a few years ago to change the rule from “queer men can’t give blood at all” to a “year of abstinence and you can donate.” Þórólfur Guðnason, the Chief Epidemiologist was talking about a 3 to 4-month period because that is what other Nordic countries have in place. I thought that had gone through, that something had gone through!”

“Between the blood bank itself and the Ministry of Health, I wasn’t sure which one was discriminatory. It seems at the end of the day it stops with the government though.”

The rules, however, have not changed. At the moment Blóðbankinn’s (the blood bank) criteria for all blood donors specify you should not donate if you are a “male and have had sexual contact with another male” and that blood donation will be deferred for 12 months if you’re a “woman and have had sexual contact with a male who has had sexual contact with a male.” This puts Iceland far behind all the other Nordic nations, France, Canada, and the US who all institute a 3 to 6-month abstinence policy for queer men who wish to donate blood.

Don’t misinterpret the headlines

What perplexed Heiðrún the most while researching the topic was just how much it looked like Iceland had already taken care of this. When she was googling and researching all of the headlines and news about the subject seemed to imply Iceland was already moving to a 1-year abstinence rule or “looking into” the 3 to 4-month policy. “I was so surprised that nothing happened from all that attention. That’s why I wanted to do this. The search results come up with headlines that read “gay men are finally able to give blood,” but it’s all about the proposals. It’s all of these huge positive titles like “Proposals for a bill for a one year period blah blah blah” and it hasn’t gone through. And it’s been years which is annoying! If you’re just a normal person in Iceland just googling this and you saw all of these articles you’d just think it’s already done, it’s already taken care of, like there’s nothing to talk about anymore and the rules were actually changed,” says Heiðrún.

Dirty Blood

The donation rules as they’re currently written also group all queer men in a monolith of “dirty blood,” says Heiðrún. “It just puts all queer men under the same umbrella. It doesn’t matter if you’ve been with the same man in a monogamous relationship for 20 years, only slept with that man, both HIV negative, it doesn’t matter. It’s the same rule for everyone because there’s still a stigma that queer men sleep around all the time,” she clarifies. In her eyes, this is the root of why queer men, in general, are still stigmatized: “That’s why I wanted to say “dirty blood” on the piece because queer mens’ blood is still considered dirty in general.”

The message she hears from the policy is that “queer men are soiled, dangerous, and lesser than.” However, in her eyes the “issue doesn’t exist in a vacuum.” The broader implication is that “it’s not about whether or not you can donate or not, it’s about the government telling you that you’re lesser than others based on who you’re sleeping with,” says Heiðrún.

Where’s that proposal Willum?

Progress in this area is possible. Canada recently changed its blood donation policy from a 3-month celibacy period to no waiting period at all. Canadian Blood Services, the organization running banks in the country, will also stop asking donors about their sexual orientation in September and instead ask if donors have engaged in any higher-risk sexual behaviors. This comes after years of pressure on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau who campaigned on the promise to lift the homophobic rule.

In Iceland, a proposal was made in 2021 by Svandís Svavarsdóttir, the previous Minister of Health, due to take effect in January of this year if it had been approved. Months later and there’s not much more progress happening on the issue other than a solid “we’re looking into it” and “there’s a lot to consider” from current Minister of Health Willum Þór Þórsson.

“That’s why I wanted to say “dirty blood” on the piece because queer mens’ blood is still considered dirty in general.”

In a legislative session on the 31st of January, Þórsson was questioned by Pirate Party member Andrés Ingi Jónsson about the policy and mentioned that for the law to be changed considerations about testing and screening needed to be made: “some changes have had to be made; risk analysis and primarily to introduce blood screening with a so-called nucleic acid test or NAT. In addition to such blood screening, erythropoietin clearance must be performed.” According to Þórsson, the proposal would be ready in “April/May.” The month of May is half over with no update on the discussion from January.

Heiðrún sees through the politics and wants to see change demanded. That’s why her piece is so bold. “Do people realize that this is the same, that the law hasn’t changed and queer men are still banned for life?” she asks. The discrimination queer men specifically face when donating also overlooks the fact that anyone, regardless of their gender or sexual orientation, can carry STIs in their blood and anyone can be as sexually active as queer men are portrayed to be.

Biohazard regardless of the donor

Heiðrún says Sigurður, a queer registered nurse who donated his own blood for the project, told her using protective equipment was a must from the beginning. Regardless of if it was queer blood or not “working with blood, I have to have gloves and a mask and be protected because blood is a biohazard in general,” she says.

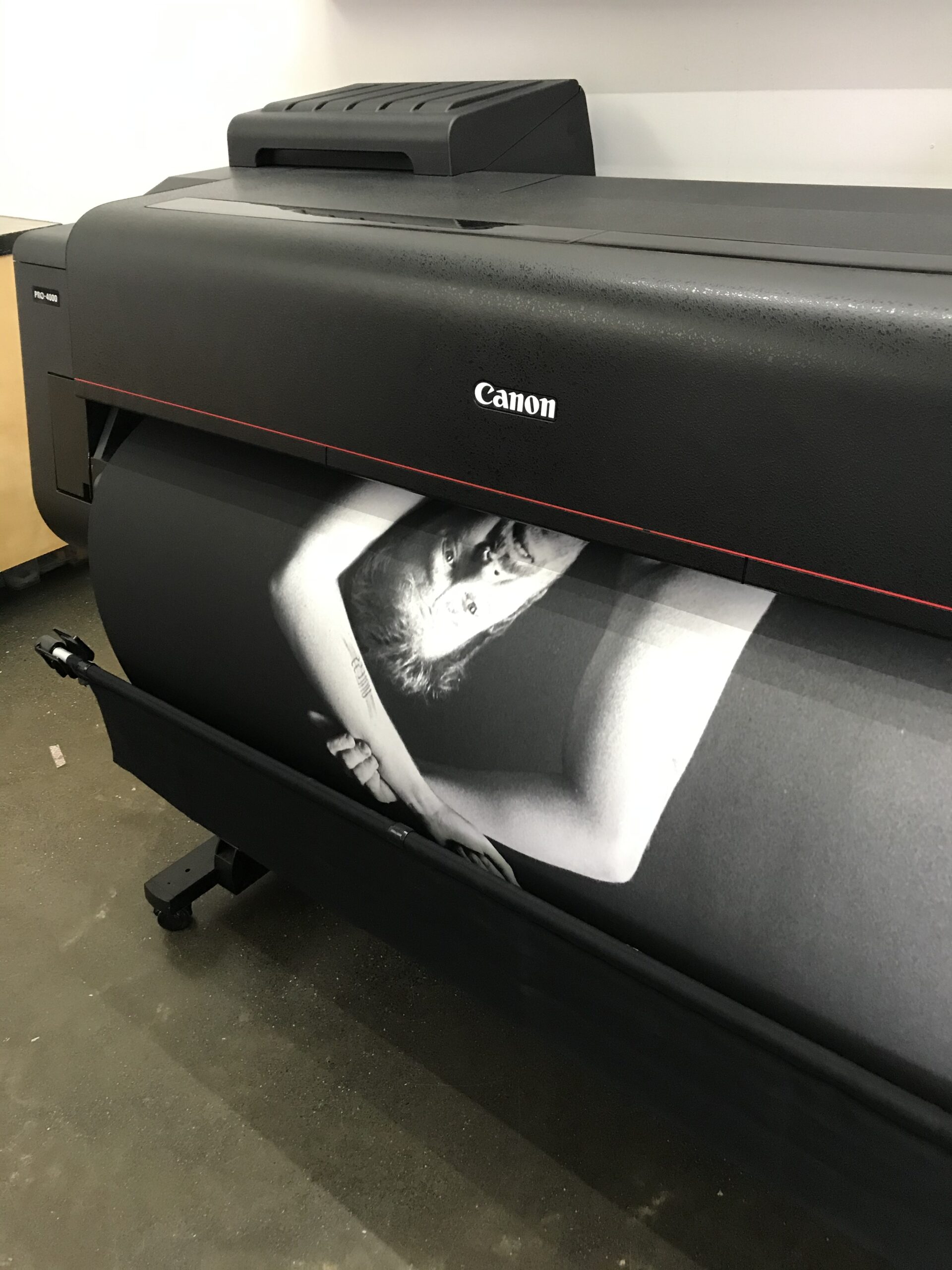

As a photographer and artist, this was her first time working with blood as a medium. “I’m just a student. This is just my first year in school. I was quite scared. I was also scared I wouldn’t have enough blood to use,” she says. Despite any worries, her teacher encouraged her because of the message it would send; “it was easier than I thought. I was thinking about mixing paint with the blood to get the color right but I didn’t have to. I did some tests and what I used is just 100% blood. Conceptually it’s also a lot stronger if it’s just blood, ”she clarifies.

“I also realize that I’m a lesbian, this is not about me, this doesn’t affect me personally but it’s super important to shine a light on the issue.”

When coming up with the idea for her final project she also wondered how she would acquire queer blood in the first place. “I originally just wanted to use red paint but my teacher told me it would have a stronger message if it was real.” says Heiðrún.

“It was surprisingly easy to get queer blood,” she laughs. “I’ve been a part of the queer community and involved with activism for so long so people know that I approach things respectfully. So I was very happy with Siggi who was happy to donate,” she adds.

Bigger than just one exhibition

Though Heiðrún knows the story of her photo and the blood on it will have an impact, she realizes the conversation is bigger than just one photo: “I’m thinking in broader terms. This is the exhibition I’m doing for school. There’s a message I’m trying to get across,” she says. “This is how I’ve been doing activism, this is how you change people’s minds.”

Other works in the exhibition cover all kinds of topics like mental illness, motherhood, immigration, meditation, sustainability, and femininity. Each of the students is taking something they’ve already been working on and pushing it a step further.

Has the conversation around HIV and blood donation changed?

Heiðrún is happy to be shining a light on blood “cleanliness” and the discrimination that still exists. With a call to action she says “I also realize that I’m a lesbian, this is not about me, this doesn’t affect me personally but it’s super important to shine a light on the issue. There are so many people who have been talking about this activism and changing the blood donation rules and doing really important work, but it’s still the same as it was 20 years ago. The HIV stigma is still around 40 years later. We’re still dealing with it even though the situation is totally different. We have medicine. It’s not a death sentence anymore. It’s not just queer men who get it but that stigma is still there. Hopefully, people are more willing to listen now.”