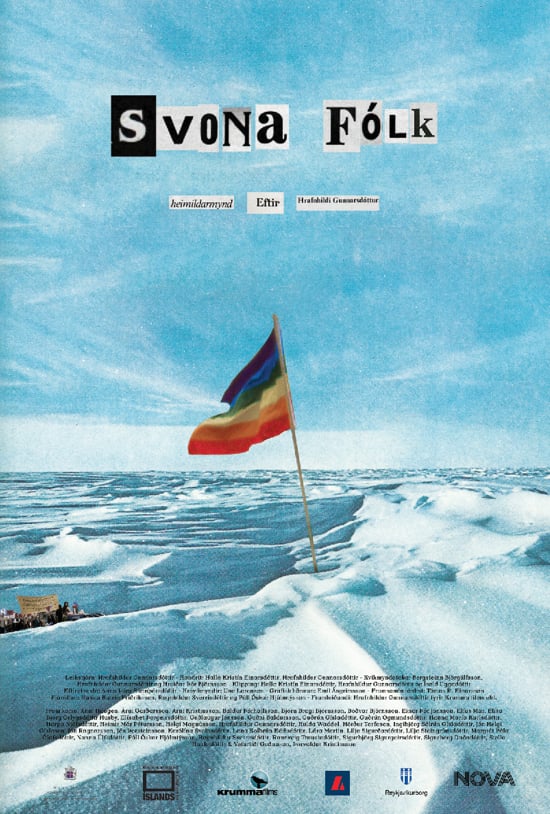

Full length material from the documentary series Svona Fólk available online.

The 2019 documentary series Svona Fólk detailed the fight for queer rights in Iceland and told the stories of countless LGBT+ Icelanders. Hrafnhildur Gunnarsdóttir, the creator of the series, is now adding the full length interview material online with new and never before seen footage from the series. Over 400 hours of footage was collected discussing the formation of Iceland’s Samtökin ‘78 Association, the beginning of Reykjavík Pride, the fight against HIV and AIDS in Iceland, and personal stories from around the island. GayIceland sat down to chat with Hrafnhildur about the series and its impact in Iceland.

On becoming a documentary filmmaker.

“I studied in the US and moved there in 1985, to study at the University of California Berkeley,” says Hrafnhildur. “I was feeling pretty disillusioned about being gay in Iceland. It was a pretty dreadful time. AIDS was starting to pop up and the gay community here was quite small and there was a lot of drinking. I just decided that I didn’t want to spend my “good years” in that kind of environment,” she says.

“Because I had just edited and presented Svona Fólk we were processing AIDS and what happened then and I had felt like I came to some kind of peace with it. Then boom, Covid hit and observing the differences was infuriating in a way.”

The movement for queer liberation and a few icons from that time drew her to the area. “I was fortunate to go to the San Francisco bay area. I had read an article, some years earlier, about Tom Ammiano who was a gay teacher in San Francisco. He later became a part of the city council and eventually ran for mayor unsuccessfully in the 1990s.” Tom became well known as an activist after founding a gay teacher’s organization which sucessfully pushed the school board to stop discriminating based on sexual orientation. He, Harvey Milk (the San Francisco city board member who was murdered by another counsilmember along with the then mayor George Moscone), and activist Hank Wilson later went on to stop legislation banning any gay person from teaching in California.

Hrafnhildur saw this movement but didn’t necessarily know how her skills and interests would align with it. “I was in the general department of UC Berkeley but I wanted to become a journalist. I became a bit disillusioned with American journalism. Although being in America taught me a lot about critical thinking, going there at age 21 wasn’t easy,” she says. “I ended up studying more photography. I’ve always been involved with photography since I was in my teenage years. From there I ended up just going into documentary filmmaking, which kind of combined the photography and journalism aspects,” says Hrafnhildur.

On the difference between Iceland and the US

While studying and living in the US she would travel back to Iceland occasionally. “I lived in the states over a period of about 14 years,” says Hrafnhildur. For her, the US government’s role in the Vietnam war didn’t make the country more appealing: “I would travel back to Iceland every so often, once, twice a year. I never intended to stay that long. I had a lot of problems with American policy, the wars. People were saying “oh it’s strange that you’re going to the US” because I was quite critical of anything that had to do with the army or wars or anything like that.

But I figured it was a much more multi-layered society and I was certainly not disappointed by what I imagined,” says Hrafnhildur. “In Berkeley and San Francisco you got to know these movements, civil disobedience and free speech. I could have gone to the midwest and had a completely different experience, but I think my choice was good to pick [the bay area].”

Hrafnhildur mentions it was good in “at least in the San Francisco area and maybe New York, it was completely different in different parts of the country. San Francisco was really a gay ghetto. That was wonderful at the time because there was just this huge presence and visibility of gay people. Nobody was wondering what anyone else thought. But it was completely isolated in that particular area. You know, you go down to San Jose or into the valley and totally different attitudes prevail.”

She says in Iceland at the time everything was very closely knit. “A lot of people were still ashamed. [LGBT+] people were in hiding. We didn’t have the strength of a community. We had just started being a little bit visible in like 1981, 1982 when the first pictures were in the media about being gay. And only one or two years later we had AIDS on our hands.” The virus was confusing because “at first we were wondering if this was some kind of attack, not quite believing that you could have a virus that would only attack gay men,” says Hrafnhildur.

“As a young person, dealing with your friends being HIV positive and then dying, it was a pretty horrific time.”

“It was totally different because of how closed and small the society was. Once the gay movement here had nothing to loose, meaning AIDS was upon us and it had to be dealt with, that’s how we became visible in the media and to the authorities, that’s when things started changing. I realized this coming back. I could see things changing. As a young person, dealing with your friends being HIV positive and then dying, it was a pretty horrific time,” she says.

On collecting personal stories

That’s when Hrafnhildur started documenting interviews with Icelanders. “The first interview was with my dear friend Björn Braga Björnsson who died a year later or so from complications of AIDS,” she says. The tone around the conversation for queer rights began to shift. “That’s when things started changing and they started pushing the politicians to investigate what the status really was for gay people here. Which resulted in the law that was passed by the parliament in 1996 ensuring gay partnership. It had a huge effect. For those of us who thought we should fight for marriage being completely dismantled, we were completely wrong. At least the government here wasn’t like the US government, Regan in particular, not even wanting to mention the word AIDS. At least it was being dealt with on an official level [in Iceland].”

On our current pandemic

Hrafnhildur says looking at the current pandemic response shows the difference between how queer people are treated and the rest of society. “It kinda makes me furious,” she says. In her view “it took a long, long time to get a realistic treatment [for AIDS]. Until the cocktail came it was twelve or thirteen years. I think it was homophobia in part that contributed to how long it took to get the proper medicine. You can see since Covid is affecting the general population, it only takes a year to find vaccination. Talk about second class citizens!”

For Hrafnhildur it was jarring to have just finished the documentary and then be in the middle of another outbreak. However, this may have changed the viewer’s perspective on public health and disease control. “Because I had just edited and presented Svona Fólk we were processing AIDS and what happened then and I had felt like I came to some kind of peace with it. Then boom, Covid hit and observing the differences was infuriating in a way,” she says.

When asked if she would have made the documentary differently now, after another pandemic Hrafnhildur says: “I might have at least hit upon those points. It became so stark looking at the different responses we gave Covid-19. How cruel can a virus be to only affect gay people, gay men in particular? And of course other “disposable” populations at the time like narcotic drug users and the black population. It was an interesting perspective to obtain after the fact.”

On the reaction from her work

At the end of the day, Svona Fólk is a huge addition to the historical register of queer life in Iceland. “I’m just happy to have finally finished the project because the first interview was taken in 1992 and the program aired in 2019. It took a long time to make. It also surprised me how it became a process for the nation to look in the mirror. Many people came up to me and said “I didn’t realize it was like that.” It seemed that what was so in our face and our experience, despite the media writing articles, was a hidden experience,” says Hrafnhildur.

Apparently, many modern Icelanders didn’t think their neighbors we’re really dealing with much adversity. “Whatever realities we were facing in terms of discrimination, they didn’t think it was really true. Now that [Svona Fólk] aired, people that didn’t believe it before suddenly saw something they hadn’t,” she says. “I have never in my life gotten such a response. People calling me out of the blue or jumping on me in the street and hugging me, giving me flowers. It was totally unexpected,” says Hrafnhildur.

“There are lots of good people working inside the national church, however there are still priests that believe marriage is only between a man and a woman but they are few and far between.”

“It definitely changed the conversation. The way which I ended up presenting the material was making sure the material was through my perspective. For one, I didn’t want to be criticized by gay people and I didn’t want to be criticized by straight people. So I just presented it from my own perspective. And I think that ended up really working as you can’t say “oh she didn’t talk about this or that” because it was just from my own experience. One of the responses I got was that people didn’t really know it had been like this, that it had been so difficult.”

On what the church said

Following the documentary, the Bishop of Iceland apologized on behalf of the National Church of Iceland. Hrafnhildur says this was a big step forward and pushed the conversation further. “The second thing was that some of the more liberal priests felt unacknowledged and they criticised me. However they were treated like the rest of the “outsiders” in the film since the film was from a gay perspective. I wanted to make one episode about the struggle with the church but I only had 5 parts to deal with a 40 year history so that whole part ended up being short. Still it shook the national church which is what matters and gay people ended up getting an apology from the bishop on behalf of the national church. There are lots of good people working inside the national church, however there are still priests that believe marriage is only between a man and a woman but they are few and far between. It took too long for the church to change. But at least it ended up happening. As a filmmaker you never know what’s going to happen, but that was definitely a positive thing,” she says.

Another story Hrafnhildur sees worthy of documenting is the relationship between Krossinn (The Cross, a religious group) and members of the LGBT+ community. “There’s a whole untold story there with Krossinn. Krossinn ran a half way house – which the authorites never should have allowed as a treatment resource – and many young gay men exiting rehab in particular ended up in there,” she says. “There are stories of gay people straight married in the church. Furthermore, I know of at least a couple of men who ended up in the program, who ended up committing suicide. So there’s that whole story that hasn’t been told… but we’ll see,” says Hrafnhildur. In a 2016 interview GayIceland’s Friðrika Benónýsdóttir chatted about Krossinn with Ragnar Birkir, an ex-member, who mentions the group wasn’t actively changing people’s sexual orientation but they encouraged people to “become their true selves.”

Even though some of the conversation was started with Svona Fólk, Hrafnhildur says she “will probably end up collecting more material about the church” because it’s a conversation that she’d like to close. For her, there’s a lot more material to work with. “We have a lot of allies in the church but I was unable to really deal with that in the series. It became like six minutes of something that could be fifty minutes. After the faux pas they made with the whole campaign with the gay Jesus they kinda took one step forward and two steps back (laughs). They just can’t help themselves.”

On making the project a reality

The series wasn’t easy for Hrafnhildur to make either. She didn’t receive much funding for it until years into the project. “Well it’s interesting because first it was about HIV and its impact. Then it became about the gay movement. I probably could have done a better job, but it became a duty. Maybe I should have filmed more here or there, typical doubts of a filmmaker. I was having such a hard time getting the project funded. It took ten years to get any reasonable amount of money for it. That was hard. And you have to carry it, carry the weight yourself and believe in yourself. When you’re at that age you’re always doubting yourself,” says Hrafnhildur.

She mentions that it was really important to document this whole time and she’s glad she did it, and she’s glad she finally managed to complete it. And there’s even more material than what made it on RÚV. “It was such a huge amount of material we decided to make it available for academics because it turns out that no one else documented these stories. I could have made a few different films with all the material that was left on the editing room floor. So I decided that I’d like to give access to it for future generations.”

Hrafnhildur says “as a matter of fact I wanted to make eight episodes, and I made five. I ended up making another film, Fjaðrafok – The Glitter Storm that chronicled the history of Hinsegindagar (Gay Pride later Reykjavik Pride), which also had a huge effect. It came out last year, but that could have been another episode in the series.

“I could have made a few different films with all the material that was left on the editing room floor. So I decided that I’d like to give access to it for future generations.”

I have an English subtitle version of the episodes, but I think for a foreign market I should make a stand alone documentary, full length – 120 minutes,” she says. The original series is long, Hrafnhildur figures “a shorter version would definitely be better for an international audience. I don’t have any plans for that, but I could end up doing it. Last year with Covid and everything being shut down it made sense to air the program for pride [on RÚV].”

Though the documentary is now complete, Hrafnhildur says the best way to continue her work is to make the material available to more people, especially the younger generation of Icelanders in school. “For me right now, I want to complete the website (svonafolk.is) and I was hoping that the government could help me make the series available to all schools because I get lots of requests to show it in schools but they have no funding. I was hoping that I could finance a sort of second life online for the schools, but I’m not sure.” The importance of the interviews Hrafnhildur collected plays out as a case study for future generations. The context of what life was like for queer Icelanders before will prove invaluable when fighting for our rights in the future.

To find out more about Hrafnhildur, Krumma Films, and Svona Fólk, check out the links here:

Svona Fólk on RÚV

Svona Fólk on Vimeo

Svona Fólk website with full interviews

Krumma Films