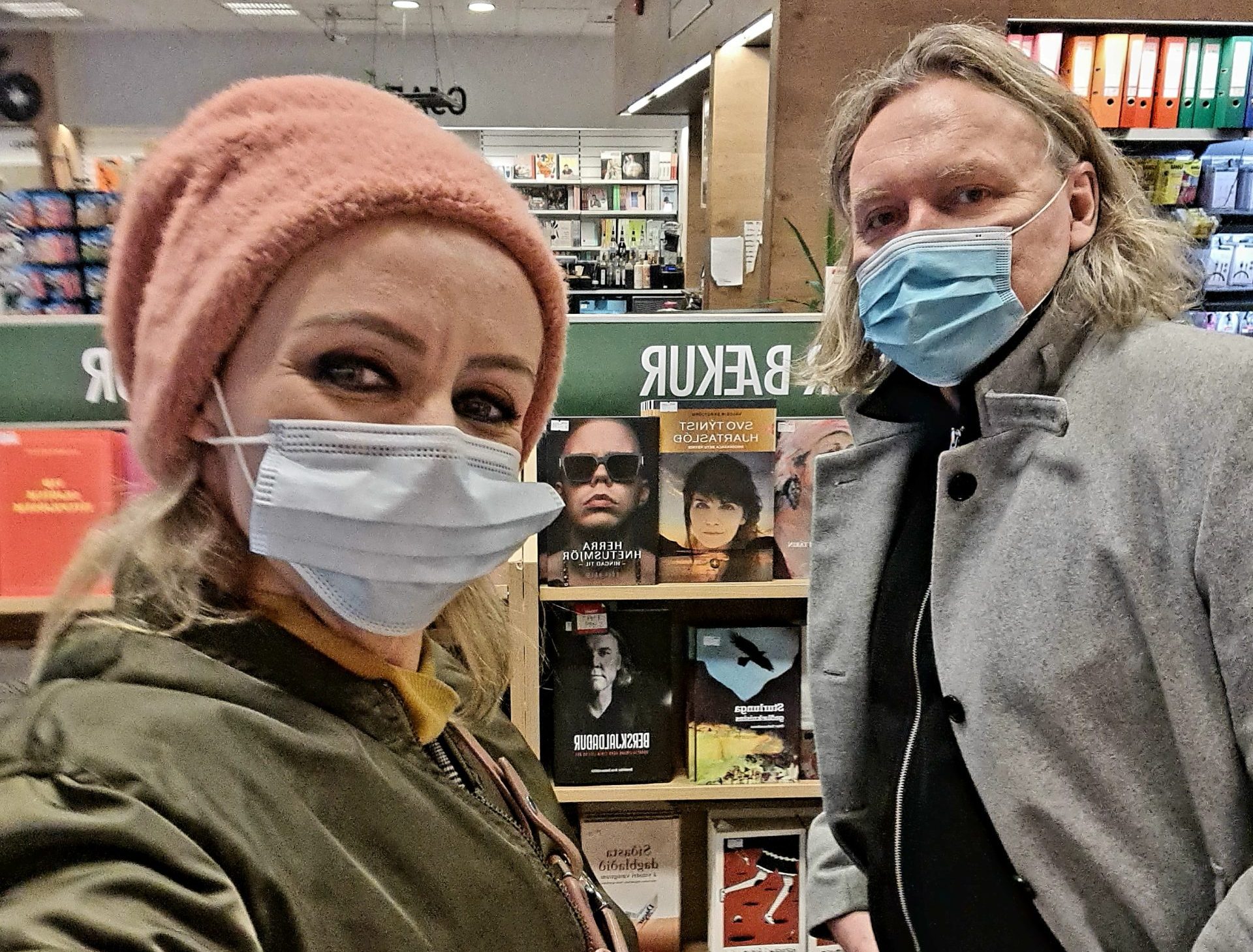

Icelanders may recognize Einar Þór Jónsson for his advocacy about LGBTQI+ issues as the executive director of HIV Iceland and the chairman of the national mental health association. Now, his extraordinary life story is available for everyone to read in the book Berskjaldaður by journalist Gunnhildur Arna Gunnarsdóttir.

The two met a couple years ago after Einar read an article Gunnhildur wrote in the Icelandic Medical Journal about PrEP, a drug that prevents HIV infection. Einar wanted to publish the article on HIV Iceland’s website, and he also asked for Gunnhildur’s help writing an article for the organization’s annual journal. The two quickly became friends, and Einar asked if she would write his biography.

The story starts at the beginning, when Einar was a child in the small town of Bolungarvík in the Westfjords, where his father was an important figure in the local fishing industry.

“People thought that I would be the one who would take over,” Einar says. “Then my mother died. I was lonely, and I was a strange boy. I was trying to come out of the closet, but it was impossible to come out in Iceland in the eighties. You had to leave the country to do that and to live your life.”

So Einar moved to London, where he met his first lover.

“I met this beautiful man,” he says. “He probably infected me with HIV, because shortly after I became ill. It wasn’t too long until he died of AIDS, and then I came back to Iceland.”

Berskjaldaður tells the story of Einar’s life with HIV, but also other challenges he’s experienced, such as his brother’s death by suicide, his partner’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, and the death of his grandson. “People think this is a book about trauma,” Einar says. “Of course it’s sad, but I feel it’s a lot more than that. I’d like people to see brightness and resiliency in this story too.”

“I don’t like to be a bitter old man always talking about what was done wrong in those days, but that’s the truth and people should understand that.”

When Einar asked Gunnhildur to write his biography it was a “dream come true,” the writer says. “I’ve been a journalist for about 15 years and I’ve had the dream of writing a book, but I had never done it before.”

“I was a little amazed by how trusting he was,” she says about Einar. “For months I didn’t show him anything I was writing. I hadn’t decided what the style should be. Should I use first person, or the third? In the end I mixed it up, so that Einar wouldn’t have to tell the reader everything. It’s more like a story than him explaining his life.”

“I trusted her a lot,” Einar says. “I told her a lot of things that I’ve never told anyone else.” Einar says that despite their differences, he and Gunnhildur have a lot in common in their family histories and they share a similar worldview. “Our fathers were both involved in the small communities we came from,” he explains. “They were both very conservative and old fashioned men, and they were brought up thinking that the world is black and white.”

Although she had written about HIV for the medical journal, Gunnhildur says she learned a lot while writing Einar’s story. “I was just a child in the eighties, and I remember the fear and everything, but I never lived it,” she says, referring to the AIDS epidemic. Like Einar, Gunnhildur also grew up in a small fishing village in the northern part of West fjord. “There was a guy a little older than me who moved from the town where I’m from and caught the virus and died at the age of thirty,” she says. “That was the only connection I had to the virus.”

Gunnhildur says Einar sometimes jokes about their differences. “I’m not gay. I have three children. I live in the suburbs. We are both from small fishing villages, but that’s actually probably the only thing that we have in common,” Gunnhildur explains. “But still we believe that we are very much alike. When we talk about our feelings, we think very much alike.”

In addition to Einar’s story, the book weaves together the stories of others living with HIV in Iceland. “We met people who experienced these times with Einar. Some of the stories are in the book,” Gunnhildur says. “It was heartbreaking to hear of young men in their twenties having special clothes for funerals, and how they spent Fridays at the funerals of their friends and lovers.”

“But we should not forget that the HIV virus in the eighties and nineties was nothing like COVID. HIV was filled with guilt, prejudice and dislike of people who only wanted to love and be loved.”

Of course, the release of Berskjaldaður coincides with another pandemic that is affecting millions of people around the world. Not only is the book’s release framed by the specter of the COVID-19 pandemic, but both Gunnhildur and Einar contracted COVID-19 in the months before the book’s publication. Gunnhildur says that having the virus helped her better understand what it may have felt like to be diagnosed with HIV.

“I think people now understand the fear of catching a virus,” she says. “But we should not forget that the HIV virus in the eighties and nineties was nothing like COVID. HIV was filled with guilt, prejudice and dislike of people who only wanted to love and be loved.”

Gunnhildur says she hopes people who read their book understand the negative impact that discrimination and stigma has on people. “If you put certain groups of people aside, it not only affects their life but it affects their life choices,” she explains. “I hope people will see that if we all just get to be who we are, it makes our life easier and better. We need to make room for us all.”

“This book is about gay men in the eighties and nineties infected with HIV, the discrimination and stigma we experienced, the loneliness, and how we were treated like we were less than others,” Einar adds. “I don’t like to be a bitter old man always talking about what was done wrong in those days, but that’s the truth and people should understand that.”

Although Berskjaldaður is currently only available in Icelandic, Gunnhildur says she hopes to have it one day translated into English.