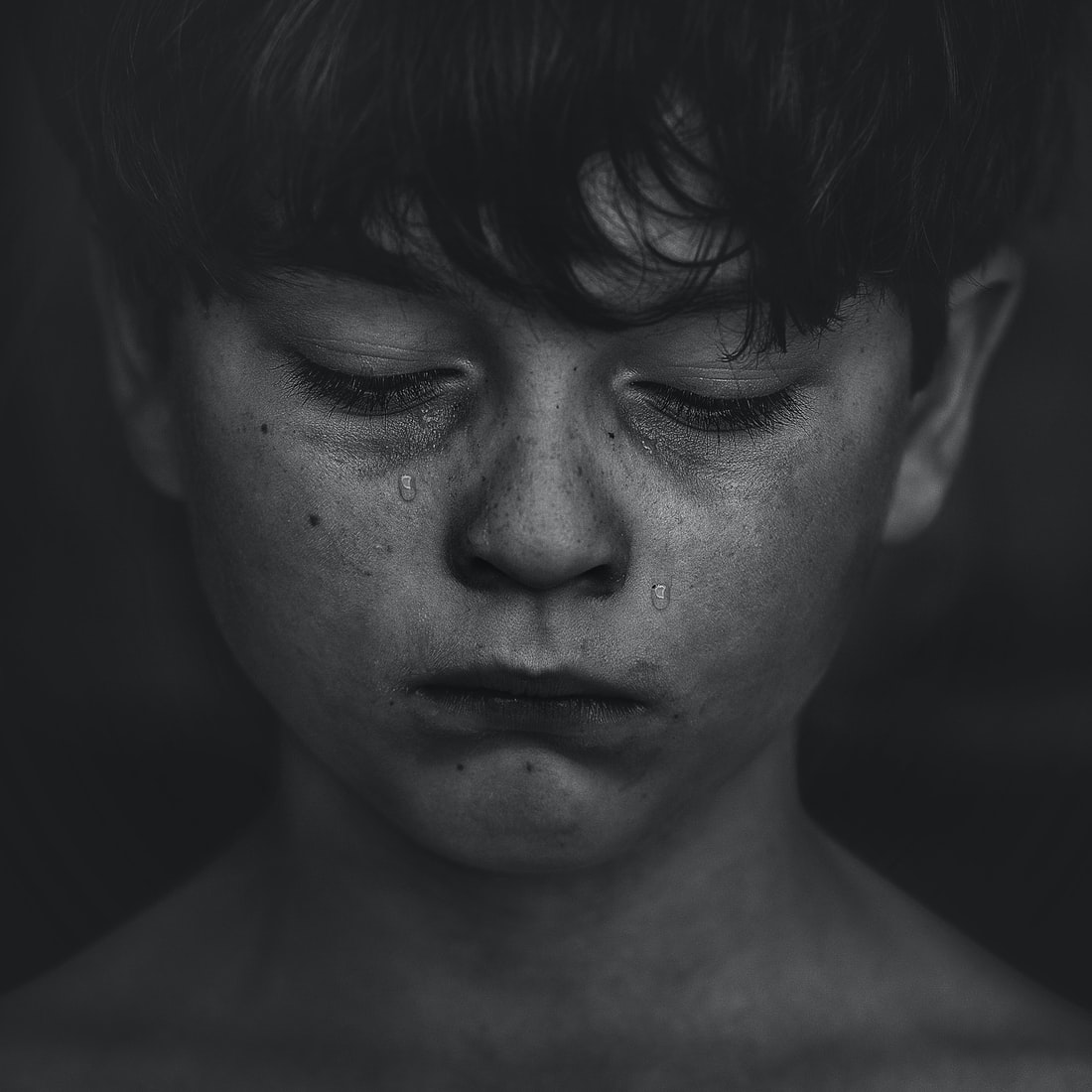

Over the course of the past month, a national conversation on bullying has brought to light personal stories from across Iceland. Celebrities and Facebook groupers alike have been bringing up the topic of bullying and its long term effects through heartfelt and private tales of their childhood years being bullied. The “trend” all began with an alarming post from Sigríður Elín Ásmundsdóttir, who’s son Óliver was being bullied incessantly both in and out of school.

Relentless bullying turns serious

Her post detailed the extent of what Óliver was facing at Sjálandskóli in Garðabær and at football practice. The bullying had been occurring for such a long time without intervention that Sigríður chose to take her son out of Sjálandskoli and switch him to a football team in neighboring Hafnarfjörður. More than just comments or teasing, Óliver would walk home with no shoes after abusers threw them over tall fences and they even threatened to kill his dog. Sigríður said she knew it was time to really step in after she overheard him talking to a friend on the phone and saying “I feel so bad at school I want to die.”

For this 11 year old, the bullying just wasn’t stopping. Although Óliver’s school has strict policies on bullying and statements have even been made by the administration and Minister of Education and Culture, the bullying still went unpunished. “In my opinion, it is an unacceptable solution to the case that the victim has to move out of their neighborhood school to get rid of bullying. We must build a system that has the capacity to ensure a successful solution. That’s my next task!” said Lilja D. Alfreðsdóttir, Minister of Education and Culture.

What’s the solution moving forward?

In most cases of bullying, it’s difficult for parents, coaches, and teachers to intervene every time if they’re not directly aware of the problem happening before them. In addition, repetitive and incessant bullying is often hardest to see because it can be more subtle and happen out of sight from guardians and teachers. More and more common for kids of the newest generations are different forms of cyberbullying, which are nearly impossible for parents to supervise between Snapchats and Tik Tok comments.

There’s a lot of progress to be made

This reginited conversation surrounding bullying comes at a time when research and data are pointing to an increase in the struggles young Icelanders are facing. One-third of LGBT+ youth feel unsafe at school in Iceland despite countless projects to prevent bullying, increased education surrounding queer issues and queer history, and the passage of more and more legal acts protecting LGBT+ people.

Iceland moved up 4 places from 18th to 14th on ILGA’s index of equality among the 49 European nations, but still has an enormous amount of work to do before claiming 1st place.

Tryggvi Hjaltason, of CCP, was chatting with radio show Armageddon about his research and said that we’re leaving young Icelandic boys behind the most. Registration of men into University has been dropping and it’s not attributable to a changed ratio with more women registering. Women registering to University is on average for the OECD countries. The men’s registration levels are the lowest of all OECD countries. Currently, Iceland has the highest diagnosis of ADHD among boys in Nordic countries, and we medicate our kids the most of all countries in Europe. However this medication isn’t helping the boys, because surveys show that they feel worse, are less likely to get praise from their teachers, are bored in school and get lower grades than before.

34.4% of boys in Iceland can’t read well enough when they graduate from Elementary school. This is 2 times higher than the percentage of girls, and much higher than in other countries. Icelandic boys also score below average in all subjects in PISA surveys, not just some subjects like in other countries, but in all subjects. Iceland is the only Nordic country that scores under average in all subjects. Icelandic girls consistently score higher than boys in standardized tests in 4th grade, and the difference in grades between the genders steadily increases the longer they are in the education system. This data all comes from publicly available databases including the Ministry of Education, Surgeon General, OECD, PISA, Unicef, WHO, and Nordic databases.

With all of these factors, Tryggvi says he doesn’t have the solution, he’s just making us aware of the issues and is a concerned parent as well. Bullying doesn’t add to these problems. If anything, the Icelandic school system is actively trying to find a solution for keeping young Icelanders healthy, focused, and learning in a positive school environment. For kids like Óliver, the last thing they need is to be distracted from their studies and discouraged from pursuing higher education.

Icelandic celebrities and politicians come out in support

In reaction to the news about Óliver, national football team player Jón Daði Böðvarsson made a statement in solidarity with Óliver saying “are boys with an inferiority complex harassing you? Let me know, friend. I was in exactly the same situation as you at your age.”

Even the President of Iceland, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson, weighed in with support as he has in the past many times supported action against bullying. In a 2017 speech Guðni noted “certainly I have nothing to complain about, I was not bullied and I did not take an active part in it, I was taught not to tease, not to name names. But I witnessed bullying and I could have done better, I could have played more often with one of my classmates who did not always fit in well enough with the group. I could also have followed the example of a handsome boy who was a popular magician, a great athlete, and made the suggestion that people should not attack his friend who was a little different from the others – and who is not. ” Guðni also works closely with Barnaheill’s prevention project against bullying Vináttu and has supported the cause publicly for years.

To hear what the queer community was saying in the greater discussion about bullying, GayIceland chatted with a few well-known Icelandic queer icons to hear their personal stories and talk about how we as a community can combat bullying.

Daniel Oliver, musician and soup master

In a Facebook post Daniel Oliver, one of Iceland’s Eurovision stars, opened up about the bullying he faced as a child and how it’s still affecting him today. His status, which shared yet another article about bullying from Jóhanna Ósk Þrastardóttir, included themes of exclusion, prejudice, and “fitting in with the norm” for safety. Daniel elaborated by saying “today I find it uncomfortable to stand out from the crowd, find it difficult to lead my boyfriend in public, and just generally have a hard time being in a large crowd, often wary when I meet heterosexual men in groups. I sometimes allow myself to be a colorful character but it is very monitored.”

Casual harassment

For him, most of the bullying he experienced wasn’t bloody hits, death threats to his dog, or beatings; it was casual exclusion and things that would go unnoticed by teachers or parents. One time, the teacher did notice and instead of intervening they joined in! “I was never really good at playing ball-sports for example and my gym teacher was very much into ball sports so I got left out and made fun of with embarrassing remarks about throwing like a girl, being a faggot and stupid stuff like that. I remember my teacher taking part in the bullying and taking part in the name calling.” For Daniel, humiliation came from even the authority figure in the room: “One time I was late to gym class. I must have been around 12 years old. I had forgotten to change clothes and came to the sports hall in my regular clothes so he (the gym teacher) made me strip down in front of everybody. The guys were laughing but the girls weren’t for some reason. They understood how humiliating it was.”

To open up about these things through a post on Facebook or an interview was difficult for Daniel. “I’m honestly not comfortable talking about this. I think their behavior was caused by peer pressure and a general fear of things that are different, and I was different. I was more feminine and usually very confident actually which made them even more determined to break me I think. I got beaten up by a guy who didn’t like me hanging out with a girl he had a crush on. It’s so stupid to think about this now but I shiver just at the thought of it.”

Changing yourself to fit in

Eventually, after all this harassment from peers in school and even the teachers, Daniel couldn’t take it anymore and started to push himself into “the norm” for safety. When leaving elementary school and entering high school, Daniel changed his physical appearance, style, or clothes to make himself less of a target. “I remember coming in ready for a new chapter. My confidence had taken a big hit so I really just wanted no drama and I just felt it would be easier if I just fit in. I had always dressed up quite uniquely and colorful but I couldn’t be bothered with the name calling and unnecessary remarks about it so I just went to black and blue. It was fine in the beginning but honestly looking back on it I feel like I lost my edge. I was very careful with how I spoke and what I shared with people,” says Daniel.

To combat bullying as a kid, Daniel recommends mustering up some bravery to fight back with words and be vocal. His advice for a kid like Óliver is “to stand [your] ground more. Call out the injustices and put those who are bullying in their place by calling them out on it and of course tell people/teachers/friends about what’s going on so they can step in if necessary.”

The queer experience

When it comes to the queer experince of being bullied, the conversation becomes a bit more complicated. Although many young kids of all genders face bullying from classmates and peers, kids that are in any way perceived to be outside of the binary of masculinity and femininity have a harder time. For many of them it’s an internal struggle between hiding their true self and being less obvious about their attraction toward a member of the same sex or gender expression, because if that is exposed they face backlash for it. Daniel agrees “I think that just by being queer and not hiding it takes enormous bravery. There’s still a long way to go. For many straight people it’s still something they know about and accept up to a certain point where there is a “it’s fine but don’t shove it in our faces” attitude which makes you wanna hide and suppress a part of you that is and feels very normal to you. And it is…. Normal.”

Harassment abroad

Daniel also spends a lot of his time now in Sweden and notes that it’s no better or worse there. Queer friends of his still face harassment and abuse in Stockholm and Reykjavik. “I feel more at ease when I’m home in Iceland I suppose. It’s my home country and thankfully I feel very safe here. Stockholm is more of a multi-cultural capital so you have to be more careful in general. I’ve had friends that have been beat up brutally outside of a gay club in Stockholm but those incedents are rare thankfully,” says Daniel. Even though Iceland and Sweden are 14th and 11th respectively on the European index for LGBT+ equality and protection, it doesn’t change the culture much for an abuser looking to demean or harass a member of the community. There are still very large targets on our backs from all angles.

“I think that just by being queer and not hiding it takes enormous bravery.”

Turning negativity into positivity

For Daniel, the best way he can channel all of this pent up negative energy from bullying and prejudice is to create something positive to put out into the world. Through his music, he’s better able to express himself and communicate his truth: “I think it influences my music in terms of wanting to empower people and my songs are deeply personal. At least these days. I don’t necessarily write or sing about the troubles of being gay but I create songs mostly about love so I guess everybody can relate to them in a sense.”

A sneak peak of the track list via Daniel Oliver

Speaking of his music, Daniel just returned to Iceland after a stint in Sweden recording a new album he’s excited to share. On Wednesday last week he posted “[Today’s] the last day in the studio here in Stockholm. My album is almost ready and I look forward to coming home, quarantining with my kitty and celebrating Christmas! I was supposed to be having a Christmas concert this weekend (my first) but it changed out of nowhere and I just did what I do best in a crisis, poured myself into work and made something. This time it is a solo album and something I will be proud of until the last day!”

To get to know Daniel better you can find him and his music here or here and follow him on Twitter or Instagram.

The magical Alda Villiljós

In a facebook post of their own, Alda Villiljós recounted stories of bullying that’s still affecting them to this day. Alda has been a community leader and activist for many years through their work with Trans Ísland, Samtökin ‘78, and Non-Binary Iceland (Kynsegin Ísland). Speaking out about bullying, Alda opened up about the relationship they’ve been building with their inner child. Through the transformative process of therapy and really communicating with their past self, Alda has reconciled their inner child with who they are today. “I’ve been doing some very intense work with my therapist, including finally admitting the amount of damage school bullying did on my psyche,” says Alda.

It’s not that bad, right?

For Alda growing up with bullying wasn’t that bad compared to stories they heard of other kids facing more abusive bullies. This made it easier to think “well I actually have it pretty good,” which minimized the trauma that they did go through. Adult Alda says it’s super important to recognize that just because you were bullied less than other kids in your class or in your age, your experience is still just as valid and has the same impact on your life. Sadly, it’s common for many victims of all types of abuse who compare their abuse to other kinds they see and say “well I didn’t have it that bad.”

Catholic school blues

In primary school Alda attended Landakotsskóli, a Catholic school. They said this isolated them a bit as a teen because the school didn’t have the same funding to take kids on trips that public schools went on. Even the class size was smaller, just one group for each grade. This made it easier for bullying to be concentrated in one room instead of spread across a larger grade. ”I came into the class in 2nd grade so everyone else had already bonded for 1st grade. I was already this outsider,“ says Alda.

“From then on I was always collecting other new kids into my group as soon as they arrived.” Alda attended the school because they were gifted in reading and other skills beyond most kids their age, so in a way they were ostracized for that. Then there was the bullying for being anything remotely queer. “My friend remembers this so much better than me and she said there was a lot of homophobic bullying, which she was like more androgenous presenting so she got more of the attacks for that.” Sadly, Landakotsskóli has its own history of mistreatment with faculty members abusing students which has haunted the school, even when Alda was attending in the 90’s.

It gets better and therapy really helps

Following primary school, Alda moved on to Menntaskóli Hamrahlíð and really started to blossom. “I came out bisexual in my first year of Menntaskóli so it was all uphill from there,” says Alda.

They walk us through how these traumatic experiences can really stay buried with us for years. “I’ve got an incredible therapist and she uses a model that’s called Ego State, and the idea is that when you have a traumatic experience, let’s say even you’re five years old and you get lost in the mall away from your mom … That’s a traumatic experience. When that happens a part of the brain gets stuck in that moment as its own thing and then later on when you’re an adult and you’re at a festival and get separated from your friends and all of the sudden this five year old kid takes over your brian, and that’s why you panic.” Through the hard work of inner reflection and therapy, Alda has made incredible progress toward repairing these parts of their past.

“There was a lot of homophobic bullying, which she was like more androgenous presenting so she got more of the attacks for that.”

Hey little me, how ya doing?

For Alda, the best part about analyzing all this was creating a special relationship with their inner child, their past self. In their original Facebook post they elaborated about “when I first started talking to this part of me just over a year ago, it took such a long time for them to accept that we’re the same person. They could never have imagined someone so radically different, living out so many identities and looks and projects they hardly dared daydream about for fear of being bullied for it. It wasn’t until my therapist suggested my inner child might want to wear something else or look different, that it clicked for the inner child. The overwhelming and pure sense of freedom as we cut their hair, got cool, masculine or gender neutral clothing. After that they were ready to accept me as the present version of them” says Alda.

Creating their own language

After moving back to Iceland in 2014, Alda started brainstorming non-gendered language. Having learned and used pronouns in English and Swedish, Alda was surprised to see how little Icelandic had to work with and was intimidated to move back as someone who’s non-binary. “At the time it was typical to simply use “it” (það) for someone who didn’t fit into either “he” (hann) or “she” (hún)” says Alda. To improve this situation, they got together a simple group chat to discuss the 3rd gender pronoun in Icelandic. This conversation later snowballed into community organizing and Alda founded Non Binary Iceland (Kynsegin Ísland). An article they wrote later ignited the conversation on this and Iceland’s 3rd pronoun was born, “hán” (they/them).

Today, that work continues through many organizations and Alda’s projects with Samtökin ‘78. As an activist, they helped start a word competition called Hýryrði in 2015 to crowdsource queer words in Icelandic. These words have made their way into mainstream use, publications, and been used in the rule of law to better describe more people in the queer family. The competition is now running again to help generate better terminology for non-binary people in Icelandic.

To get to know Alda better you can find their work at:

Alda’s Activist Page

Trans Iceland

Non Binary Iceland

Namm Vegan Treats

Alda’s Photography

Witchcraft Podcast

Astrology and Witchy Things

Þorbjörg Þorvaldsdóttir

Chair of the board for Samtökin ‘78 Þorbjörg Þorvaldsdóttir believes awareness in schools and more proactive parenting can help combat bullying. “In general it comes down to kids not having the social skills yet developmentally and not having good role models. Their sense of compassion and empathy is developing, but they’re trying their best to fit in. The problem when it comes to aggressive behavior also has to do with what they’re seeing at home and what they’re learning from older kids. Parents have a huge role to play and need to be mindful of what they’re saying in front of their kids, especially when it comes to LGBTQ+ issues.”

Prevention vs. reaction

Through her work at Samtökin ‘78, Þorbjörg is trying to change the narrative and create more education. Education about queer issues, says Þorbjörg, is the best way to prevent these things from happening in the first place. “The survey we conducted in 2017 and published this fall shows proof of verbal harassment in schools specifically against LGBTQ+ kids. We know anecdotally that queer people are often bullied more than other students. Since the results of the survey, the first step we took was to make the results known. For many people it was shocking to see the numbers and for example how many students saw that teachers didn’t step in when this behavior was happening” says Þorbjörg.

“It’s not your fault. You are worthy, you’re a beautiful human being, and you deserve love and respect.”

When incidents of prejudice happen and are brought to their attention, it’s already too late to change the narrative because it’s reactive. Þorbjörg explains “Samtökin ‘78 provides counseling, support, and education when there is a problem within a school or an LGBTQ+ student is in need, but of course we want to educate the whole school first to avoid these events entirely.” For most of the other students and even the adults in the room, it’s not about keeping everything peaceful all the time. “It’s about awareness and it’s about compassion. You don’t have to like everyone to be nice to them and to respect them” she says.

Planning for the future

Þorbjörg says there’s only so much progress we can make against bullying and oppression if we’re not doing this work across all schools in Iceland. “The plan is to get queer education out to more kids and more staff. For example the municipality that probably does this the best is Hafnarfjorður, where all kids in 8th grade get queer education once from someone at Samtökin ‘78. All new staff members get training as well and other staff members get updates every three years. In other municipalities, it’s up to each school individually to ask for this education. This specific training is not required for most schools” says Þorbjörg.

She elaborates, “municipalities need to take queer issues seriously and be proactive about them. They need to make sure the school environment is one where the children can thrive. That is something that can be done with a conscious effort. If you don’t do anything, things are more likely to go awry. Show an effort, make a plan.”

Representation matters

One example of a school tackling this well is Hlíðarskóli, where representation, visibility, and symbolism all combine to support LGBTQ+ students. “What they’ve done there is really cool, they have a team of teachers and staff members that are together in an LGBTQ+ unit. It’s there within other teams for the school and every teacher that’s comfortable talking about queer issues has a tiny rainbow flag in their classroom. More schools and teachers should be forming these teams,” says Þorbjörg. With the flags any student, no matter their sexual orientation or gender expression, can see that their teacher or staff member is open, willing, and supportive about these topics and it breaks down a barrier that would otherwise keep the child from coming forward.

Chin up, Óliver

When asked what she would say to a kid like Óliver being bullied in and out of school, Þorbjörg responds with sage advice:

“It’s not your fault.”

“You are worthy, you’re a beautiful human being, and you deserve love and respect.”

For more information about Þorbjörg’s work at Samtökin ‘78 click here or here. To read the full study Samtökin ‘78 conducted with GLSEN, click here (or here for Icelandic). For more information for educators and opportunities for queer education in schools, reach out to Tótla Sæmundsdóttir, Director of Education for Samtökin ‘78, here.