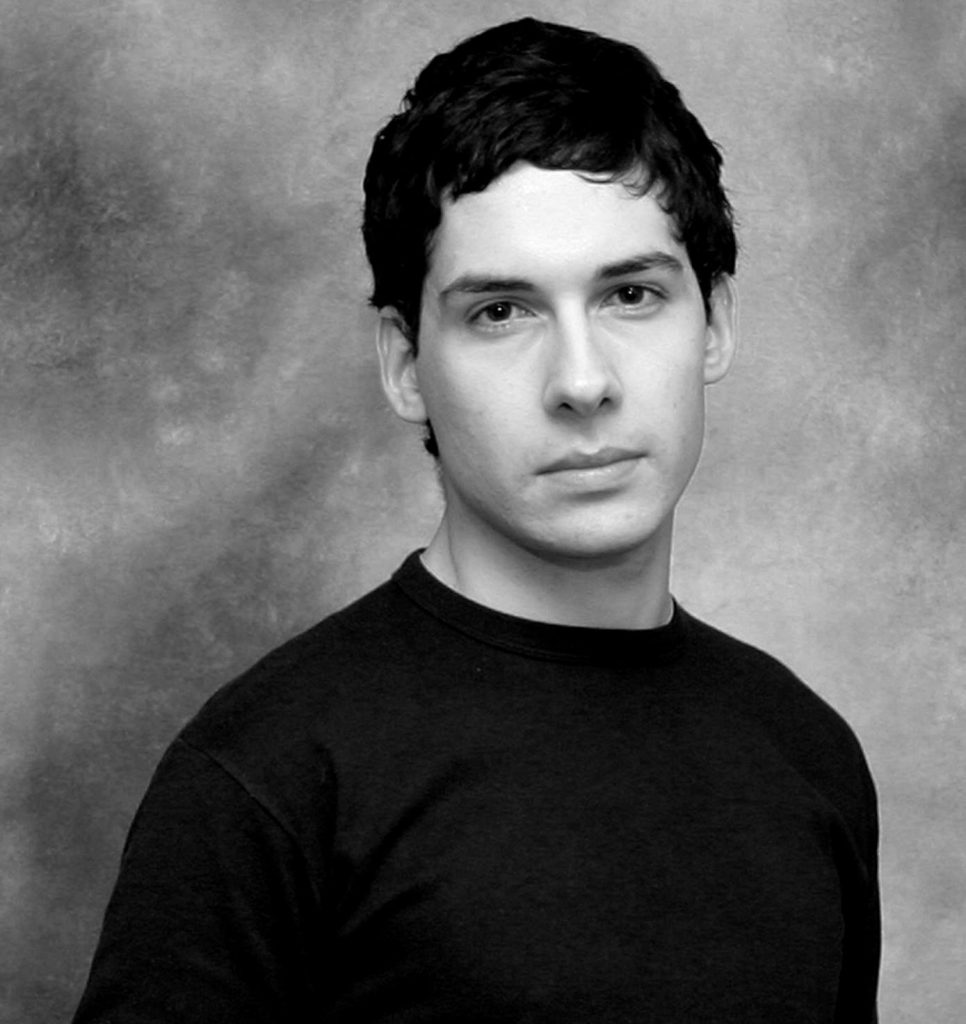

Edoardo Mastantuoni, also known by his Icelandic name Játvarður or simply Varði, is an adjunct lecturer and Head of the Department of Italian at the University of Iceland. He first visited Iceland in 2002, when he was 21 years old, and felt socially at ease immediately. He found great support from his immediate family when he came out at 17, but says that queer prejudice can at times still be found in his homeland of Italy.

“Those years represent for me the peak of romanticism. The scene and the people from Reykjavik struck me as being very ‘hip’ and utterly euphoric on weekends.”

That’s how Edoardo Mastantuoni, also known by his Icelandic name Játvarður, describes his first stay in Iceland during the Summer of 2002. He has fond memories of that Summer, being introduced to a legendary queer bar in Reykjavik.

“At that time there was a little club called Spotlight. I do not remember meeting other tourists during that Summer: Iceland was still the mysterious land of the intrepid and sturdy adventurers. My newly made Icelandic friends were keen on sharing with me the peculiarities of anything Icelandic; cuisine, landscapes, culture. The soundtrack of that Summer was the dance cover of ‘Heaven’ (‘Baby, you’re all that I want. Will you lie here in my arms?’). That song brings back many memories. I am very much a 90s boy and have never fully adapted to more recent beats,” says Játvarður, who was 21 when he first came to Reykjavik.

“ … The Italian gay scene is sophisticated and cosmopolitan. I would describe the Italian scene as ‘glossy’, glamorous. On the other hand, Reykjavik is young, euphoric, dynamic and galvanisingly out of control.”

Játvarður hails from Italy, where the queer rights movement has overcome many obstacles after years of struggling. Játvarður came out as gay when he was seventeen and found support amongst his family members.

“My family is an anti-conventional, atypical middle-class family. This allowed me to find acceptance from all members of the family. Such acceptance and understanding was, in some cases, immediate and taken for granted. For my older brother it took almost a week to digest my coming out. A week is not so bad, after all,” says Játvarður and adds that he hasn’t fully come out to his extended family.

“To some people I have come out, to others I have not. It is a feature I never concentrated upon. The act of coming out is an old adolescent memory of 1998. What mattered to me thereafter was my

studies, my academic path and the well-known search for a creative stream in which we are all involved in our lives. In short, after a mini-coming out at seventeen to the key people in my life and to my best friend, everybody else was just welcome to find out.

For example, at some point I moved to other cities to continue my education, then abroad, so a clear come-out to all uncles, aunts, very old acquaintances and the historic family friends never happened fully and the picture is a bit blurred to some. Maybe a bit less after I post this interview on Facebook,” he says with a smile.

Gays stigmatized in rural centers

In 2011, after completing his Ph.D., Játvarður was granted a scholarship by the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies and moved to Iceland permanently. There he met his spouse from Ukraine. Three years later they were married, something that would not have been possible in his homeland at the time.

“After many struggles, Italy finally recognized same-sex civil unions in 2016. This was absolutely necessary, as homosexual couples enjoyed neither legal recognition nor any legal rights whatsoever.

It was preposterous. Adoption is permitted only to opposite-sex married couples, hence there is much room for further developments and additional freedoms. A child who is much loved enjoys every prerequisite for growing up as a healthy and happy child, whoever the parents may be,” Játvarður says and adds that queer prejudice can still be found in Italy.

“Homosexuals can still occasionally be stigmatized, especially in rural centers. In cities, however, the situation is similar to that of Nordic countries, though aggressions might alas take place, sometimes.

In Italy we are, overall, more conservative than the rest of our fellow EU/Schengen countries,” he says.

“It is however important to take into consideration that it is a conservatism within European standards: Italy is European, naturally, which means that homosexuals, especially in bigger communities, are largely integrated.”

Bearing that in mind, does his family approve of his marriage?

“My parents were not present when we got married, but they have seen my husband both in Italy, when we were boyfriends, and here in Iceland, right after the marriage. In their eyes he is an acquired son. One could not wish for better.”

Wants to have a child with his husband

But if we move our attention back to Iceland, what image did Játvarður have of this country before he arrived?

“Endless green prairies where white horses run in slow-motion. Ridden by maidens in white gowns with extra-light blond hair. They resemble Jóhanna (Guðrún) in the last minute of her music video ‘Is It True?’. The maidens’ locks of hair move in slow motion in the wind. Blond children run happily. Blond farmers with checkered shirts are piling up hay in hay stacks. The sun is setting and giving the

best of its horizontal golden light. Wooden houses in the style of Árbæjarsafn sparsely dot the pastoral landscape. This is the picture. The one that every European and Asian visitor has,” he says with a chuckle.

And now you’re an adjunct lecturer and the Head of the Department of Italian at the University of Iceland. Did you find it difficult to tell your Icelandic co-workers that you’re gay?

“No, it was not difficult at all. This is a country where you feel socially at ease immediately. It may be difficult for some to make friends, but you can definitely be yourself without much perceivable prejudice. Nowadays the notion that I am gay just comes up immediately when I say: ‘My husband and I’, like Elizabeth II.

I sense that this even puts me under a better light than straight couples. People may look at me with tenderness because of my gay marriage. So, on the contrary, I can even consider myself privileged. Instead of bias, I might hold a privileged position in the eyes of my colleagues and friends. Isn’t that nice?” Játvarður says and continues on a more serious, and indeed pensive, note.

“What is sad is that I cannot make a child with my spouse. We have tried, I can assure you, both of us, to get pregnant. But to no avail.” He laughes. “Joking aside, it is psychologically daunting to consider that I cannot make a child with the person I am in love with. Think about it. How sad.”

“The club that was once on Hverfisgata had that ‘Berlin touch’ which made this city more complete. There are so many tourists in Iceland nowadays, so we should not be shy to venture into opening again a similar venue. It would … certainly take off.”

We go on to speak about the difference between the gay scene in Iceland and Italy.

“The atmosphere in the Italian gay scene is sophisticated and cosmopolitan. I would describe the Italian scene as ‘glossy’, glamorous. On the other hand, Reykjavík is young, euphoric, dynamic and galvanisingly out of control. What I particularly enjoy is when there are events organized at Iðnó,” Játvarður says and goes on.

“It is pleasant when there are more alternatives and I must admit that, upon reflection, nowadays I most of all feel the loss of the venue Reykjavik once had on Hverfisgata (Bar 46).

Some may argue that a men’s club is a form of ghettoization. But I disagree: to me such men’s clubs were an opportunity to have a decent chat, to exchange ideas, to focus on something, while enjoying the pleasure of going out for a beer.

The club that was once on Hverfisgata had that ‘Berlin touch’ which made this city more complete.

There are so many tourists in Iceland nowadays, so we should not be shy to venture into opening again a similar venue. It would represent a sign of maturity and the place would certainly take off,” he concludes.

Gay video for Italian students

Játvarður has found success in his professional life, reforming the Italian courses at the University of Iceland so that they suit everyone, from beginners to advanced students.

“Together with Stefano Rosatti, adjunct lecturer and Head of the Department of Italian for the academic year 2017-2018, we have recently reformed the entire B.A. programme so as to make it possible also for absolute beginners to enroll in the course. There is one high school in Iceland which offers courses in Italian in its curriculum on a regular basis: Menntaskólinn við Hamrahlíð. Besides welcoming students from this school, we welcome anyone else who has no prior knowledge of

Italian and intends to study it from scratch, both Icelanders and foreigners, young and old,” says the Italian lecturer, stating that the Italian courses are immensely popular.

“One of the courses, ‘Self-Directed Study in Italian’, is taught as a one-to-one course (teacher and student) or in tiny groups of three students. The course is very popular, both among Icelandic students and Erasmus students, because they establish the language level, the days of the week, the times of the lessons.

The teachers at the Italian Department are very young and dynamic and do a fantastic job in maintaining the high quality of teaching and, at the same time, keeping our classes popular among students. We have also created a video presenting our courses. A video which my husband defined as gay, by the way,” says Játvarður and bursts out laughing.

Why gay?

“He was alluding to the soft voice and the cat walk with which I moved in one of the shootings. That was totally involuntary. I was in the bookshop Bóksala Stúdenta and unable to talk with a high tone of voice. I think he also refers to the general aesthetics of the video. Whatever the case, we are most definitely gay-friendly and welcome anyone to our classes.”

“We have also created a video presenting our courses. A video which my husband defined as gay, by the way.”

Our time is coming to an end, but before I let go of Játvarður I must ask him what the future beholds for him.

“We are the forgers of our future. I do not believe in the ideal country to live in or the man of your life. There are very fine living conditions and there are people you care about. But everything else is an investment, it is what you build, it is a project shared by the person who walks by your side. Again, not the ‘ideal man’, not the man of your life, but a man you definitely care for and in the company of whom you decide to walk your life.”