The first history database about queer women is in the making in Iceland. According to the researchers this is the first time that queer women’s history will be systematically researched in Iceland and possibly the world.

“What little we know about queer people before 1960 is especially scarce when it comes to women or people of other genders,” says Íris Ellenberger, Post Doc at Centre for Humanities at the University of Iceland. “It’s hard to define who were homosexual, bisexual, transgender and so on because those terms didn’t exist then. For instance there’s no mentioning of homosexuality in Iceland till the 1950s and then it wasn’t even used about women, not until later than that. So it’s impossible to use those categories, especially since queer people before that time didn’t have these terms to define themselves and we can’t possibly know how they would have identified themselves, given the option.”

Íris and two other academics, Ásta Kristín Hafsteinsdóttir Phd student at University of Iceland and University College in Dublin and Hafdís Erla Hafsteinsdóttir recent postgraduate of gender history at Vienna University, have acquired funding for their project, with the working title “Huldukonur” (Hidden Women), beginning this fall.

“We’re going to systematically search through historical data from 1700 to 1960, for clues about women’s sexuality. Then we’ll gather the information and create an accessible database for the public, a database that can hopefully grow as we retrieve more and more information about queer history,” Íris explains.

She says the three of them got the idea when they were editing a collection of articles, about queer history in Iceland, and experienced the difficulties of finding historical data about queer women and other people perceived as female.

“We’re going to systematically search through historical data from 1700 to 1960, for clues about women’s sexuality. Then we’ll gather the information and create an accessible database for the public.”

“So the aim is to increase access to queer women’s history both for academics and anyone interested, through this database. I think that’s what mostly deters research in this area, the vast job ahead to find, let alone access the data that exists. And with women’s history especially because in general, it’s harder to find historical data about them. As a field of study, history has been more or less based on historical data where men are the main subjects and for the longest time, archives were organised in an androcentric manner so it’s often difficult to find data about women and people of other genders, except by accident. This is a huge and well-known problem when it comes to studying history from the viewpoint of others than cis men.”

The hope is that this project will become a starting point of a field that can then expand. But Íris says that the aim is not to reveal any secrets about people who can’t answer for themselves any more, or to embarrass them or their descendants.

“The emphasis is not on naming or exposing individual women and draw conclusions about whether they were queer. We’re going to look for clues, where there would have been scope for the possibility of some sort of queerness. For example, we’ve heard that in the rural culture, women sometimes farmed together, living together at a farm and running it by themselves. We can’t possibly know whether they were queer but if we find more examples of that we can at least state that that arrangement left scope for queer women to be together and undoubtedly, some of them would have used that opportunity. But we will also conduct interviews and gather stories from people who might have known some of the individuals we’ll find in the data, so it’s not all going to be guess-work but we’ll have to assess each individual case when we come across it.”

The task ahead is quite extensive. The three academics have received a funding for the project from The Centre for Gender Equality and the plan is for the database to launch at the end of next year, 2018. But, to avoid gender bias, isn’t there need for a study of queer men’s history too? “Absolutely. The reason why we’re concentrating on the women’s history now is that we found how difficult it was to find material about queer women when we were working on editing the collection of articles about queer history, so we jumped at the opportunity when the Centre for Gender Research advertised the grants. But without a doubt, we will also come across data about queer men and people of other genders as well and we’re definitely not going to dismiss that, but note it down and hopefully it can be used to expand the research later.”

“There have been similar projects … but I don’t think there’s anywhere a database similar to ours dedicated to queer women’s history .”

But perhaps there’s already more known about queer men in Icelandic history? “Indeed, as I said, history revolves more about men in general and for the longest time, it wasn’t even considered that women could have sexual desires so their sexuality was not viewed as a threat and much less studied, whereas men’s sexuality was much more talked about and studied. Some of the sexologists of the 19th century, who came up with the term “homosexuality” were homosexual themselves and therefore more interested in studying men’s sexuality, so there’s much more data about queer men.”

As far as Íris is aware, this is the first time that data concerning queer women’s history will be systematically accumulated in Iceland and possibly the world. “There have been similar projects, especially in the UK where there’s also a brilliant database of queer landmarks in Britain, but I don’t think there’s anywhere a database similar to ours dedicated to queer women’s history .”

Íris, Ásta and Hafdís will start gathering material this September and plan on beginning developing the database next autumn. The end product will not only be the database and a published article, they also intend to create some sort of teaching material for schools. And they’re pleading to the public to help them with their research so if anyone has any history data that could be of use shining a light on the lives of queer women from 1700 to 1960, people can submit information or contact them through the project’s website: https://huldukonur.wordpress.com.

The project will be kickstarted with an introduction and discussions during Reykjavik Pride. The event takes place at The Student Cellar, University of Iceland, on Friday 11th August at 12pm.

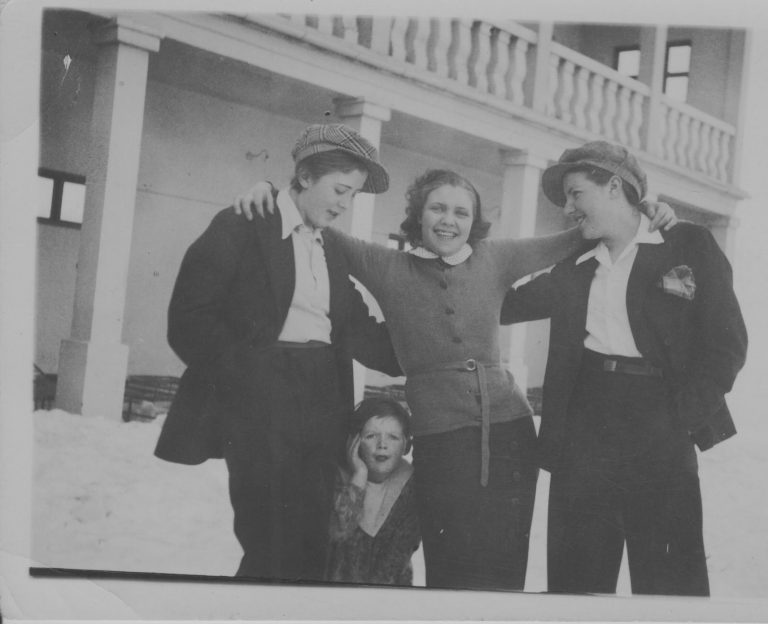

Main photo: These had obviously seen a camera before and here they look very stylish. The photo of these cheerful ladies dressed in men’s clothing is taken on a snowy day at the garden of the tuberculosis sanatorium Kristnes in Iceland.