A new Icelandic children’s book allows readers to decide whether one of the protagonists is a girl, a boy or not. The authors confess that writing the book was a challenge since it’s hard to be gender neutral in Icelandic.

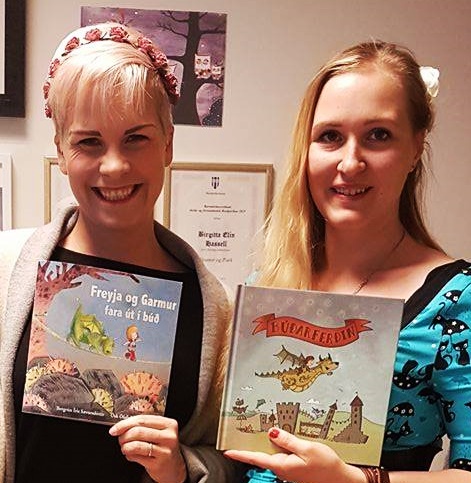

“This was a fun challenge, but quite more difficult than I had imagined. The text had to be proof read several times to eliminate all gender bias text that had some how snuck it’s way in,” says Ósk Ólafsdóttir, the author of the newly published children’s book, Búðarferðin (The Shopping Trip) along with Bergrún Íris Sævarsdóttir. One of the main character’s gender is undefined and it’s in the readers hand to decide if Blær, the character in question, is a boy, girl or gender neutral etc.

Bergrún first came up with the idea for the book in 2012, when working on a graduation project in diploma studies in drawing at The Reykjavík School of Visual Arts.

“I wanted to do a children’s book and turned to Ósk for a story since she’s an extremely imaginative mom who reads a lot for her children,” says Bergrún. “I put two and two together and sussed out that she had an idea for a story. We worked on the idea together until the book was born.”

But why did the book just see the light of day now? “The book sat in the drawer for four years, just waiting for the right publisher and the right time. I decided to re-draw all the illustrations and Ósk re-wrote the text,” Bergrún explains.

In these four years Bergrún has written three other children’s books and has always wanted them to be gender neutral. “All the characters in my previous books have been gender neutral and nameless because the Icelandic language doesn’t really offer a lot of gender neutral possibilities when it comes to names,” says Bergrún and Ósk agrees.

“Many parents … are sick of gender stereotypes and think it’s awesome to get a book that’s not only open for interpretation but also give parents the chance to talk about gender experience with their offsprings.”

“I had a vague idea that our language was quite gender bias but it still came as a surprise when I started writing the story. I found myself re-writing parts of sentences to make them gender neutral only to find that gender bias text had made it’s way into other parts of the sentences. The thing I notice the most is how hard it is to speak gender neutrally about an individual in Icelandic,” says Ósk, referring to the main character’s name, Blær.

It’s become a habit in modern society to market certain toys and books for boys and certain toys and books for girls. Designers have often made a distinction between the two genders using the color pink for girls and blue for boys. Is Búðarferðin somewhat of a counterbalance to that?

“Me and Ósk both get the chills when we hear talks about these sort of things,” says Bergrún with a passion and goes on. “Ósk has two girls who love Star Wars and Harry Potter and my two boys watch Doc McStuffins, wear pink and read every book they get their hands on without even thinking about if those books are meant for boys or girls. Children need to be children and nourish their interests, independently of their gender.”

Talking about children, do the authors feel that boys are more inclined to make Blær a boy and girls more inclined to make Blær a girl?

Ósk nods. “Yes, that seems to be most common, at least when they read the book for the first time. I heard about a kindergarten teacher who read the book for students the other day and afterwards a hefty debate arose. The class was split almost in half, where the boys saw Blær more as a boy but the girls saw Blær more as a girl. Whereas some children think it’s fun to sometimes have Blær a girl and sometimes a boy, which I think is very amusing,” she says and Bergrún adds that she feels the book serves an important purpose.

“We thought it was important that there was a book out there with a character who was vague or borderline when it came to gender for all the children who haven’t yet identified themselves within a certain gender, without the story being specifically about that. Búðarferðin is just a fairytale and the protagonist is a child. Gender is insignificant.”

A conversation piece around the house

On that note, how do children generally react to the fairytale. Do they like having the choice of determining Blær’s gender – or rejecting it altogether? “The funny thing is that kids don’t find the gender interpretation the main thing about the book and that’s of course not the main focus in the story. The children that we have talked to tend to focus more on the story itself and the imagination of the protagonist. They really don’t think about the gender neutral aspect until their parents spark up a conversation about it,” says Ósk and Bergrún adds that parents too are fond of the book.

“Many parents that I know are so sick of gender stereotypes and think it’s awesome to get a book that’s not only open for interpretation but also give parents the chance to talk about gender experience with their offsprings. When you’re done reading it I suggest asking your child: Is Blær a boy or a girl in your mind? Is Blær perhaps of another gender or somewhere in between? Does that matter? And so on,” says Bergrún.

“We thought it was important that there was a book out there with a character who was vague or borderline when it came to gender for all the children who haven’t yet identified themselves within a certain gender.”

Bergrún and Ósk don’t know of other books out there where the main character is gender neutral but has a name. “I have a massive interest in children’s book but I haven’t been able to read them all. So if any one knows of more books with gender neutral characters, open for interpretation, who also have a name, I would love to hear from them,” says Bergrún, enthusiastically.

And I of course can’t let the two go without asking them how it feels to finally have the book published after all this time?

“It’s smashing!” says Ósk and Bergrún of course agrees with a huge smile on her face.

“I think it’s wonderful seeing my first book finally published. This is a four-year old dream come true.”